The King and the Tree of Life: Evidence of Pre-Columbian Contact

Transcript of the September 2003 BMAF Conference held at Thanksgiving Point

The King and the Tree of Life: Evidence of Pre-Columbian Contact Diane Wirth: (updated Nov. 2007)

Groups of people written about in the Book of Mormon came from the Middle East. They included the Jaredites, the Nephites, the Lamanites, and the culture or cultures that were involved in bringing Mulek to this land. The Nephites, Lamanites, and Mulekites knew the customs and traditions of those in and about Jerusalem, and most likely Egypt. We know that the Book of Mormon was written in reformed Egyptian. John Tvedtnes gives a good argument that Lehi and his sons were metal workers who took their wares to various places, probably including Egypt. The Nephites knew the customs and traditions of their forefathers through scriptures, and this was, of course, from the Brass Plates of Laban. And, lastly, the Book of Mormon speaks of Lehi’s dream of the Tree of Life. We are told that it represents the love of God and especially his son, Jesus Christ.

The objective of this comparative study is to show a clear relationship between the king and the Tree of Life, or the World Tree in both Mesoamerica and the Middle East. As Latter-day Saints, we know of at least three trips from the Middle East to Mesoamerica that are the result of pre-Columbian transoceanic voyages. For those of you who are not familiar with the term Mesoamerica, it includes southern Mexico and Central America. Although Middle Eastern cultures date to a time earlier than the period commencing about 1000 B.C. in Mesoamerica that we will be considering, it is a recognized fact that the traditions were long-lasting in the New World. For example, stepped pyramids were constructed in Mesoamerica for 1500 years. Comparing this with the short time-span that has transpired between the building of log cabins and skyscrapers, you get the picture. Mesoamerican customs change very slowly compared to our fast-paced world of technology.

Mesoamerican peoples have roots going back to the early Olmec culture. Most Book of Mormon scholars believe that this culture relates to the Jaredite culture. Spanning from approximately 2000 B.C. to 300 A.D., the Olmec culture existed during the same time period as the ancient cultures of Egypt and Mesopotamia. After the demise of their far-reaching empire, many Olmec sacred traditions managed to survive through those who followed them. It will be demonstrated that Olmec concepts revolving around the king and his relationship to the World Tree, the Tree of Life (and I do use these terms interchangeably), made a substantial impression on other Mesoamerican peoples for years to come.

Referring to the role of the king in Canaan, John Gray wrote, “The king in ancient Canaan is the channel of divine blessings in nature. He is the recipient of revelation. He is also priest and personally performs sacrifice in behalf of the community.” These remarks would be just as much at home in a book on the Maya. The traditions are identical. John Gray also pointed out that in Israel, David was put in charge as the executive of divine power over forces of chaos in history. This is very significant, because this facet of kingship was of equal importance to Mesoamerican kings.

First, let us consider the concept of order as opposed to chaos. Psalms 89 in the Old Testament speaks of God as the King who triumphs over chaos. This has reference to the beginning of time, the day of creation when all was set in order. The man king had the same role. He was expected to keep the balance and order in his earthly kingdom, seeing to it that it ran as smoothly as the day the earth’s creation was accomplished. The New Year festival, which was the religious highlight of the year in ancient Israel, was held at a time when the kingship of God and his anointed king on earth were sustained in light of their ability to conquer forces of chaos and maintain a continual state of order. This was accomplished through rituals, which involved a re-enactment of the creation, symbolizing a renewal and order of all things

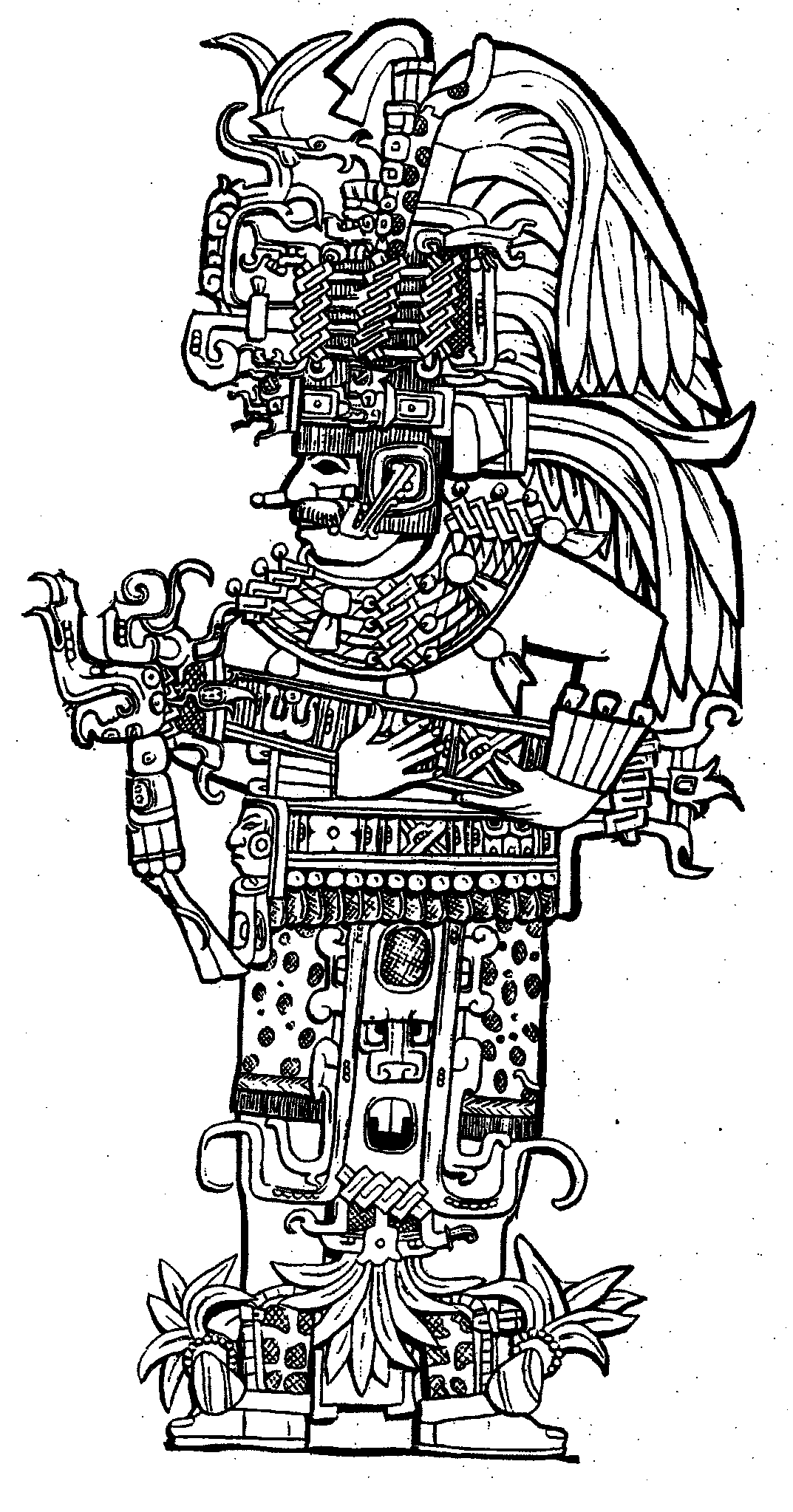

Here we have a ruler from Mesoamerica. The king was of prime importance to his people, whether in Mesoamerica or anywhere else in the ancient world where there were kings. One of the things that is unique about Mesoamerican kings, as well as kings of the Middle East, is that they were considered divine, and were messengers of divine revelation from their god or gods, as the case may be. To show a connection between kings of Mesoamerica and the Middle East, we must first examine the Sumerian and the Egyptian symbolism behind the enthroned king. Among the Sumerians, we find a close parallel with the Hebrew culture, which was a later development. In Mesopotamia, for example, more often than not, the king was considered the servant of God. Only in a few cases was the king believed to be divine. Like Israel, the same type of New Year festival was held each year to re-enact the moment of creation and to establish the king who conquers chaos as a representative of God and his revitalization of his kingdom on earth. Unlike Israel and Sumeria, where the king was considered a sacred, chosen vessel who spoke for their divine king, the pharaoh of Egypt not only spoke for his highest god, but was considered to be a literal son of god. Although the Egyptian king was considered divine, he was also a servant, for he was the one responsible to his divine father and was expected to carry out his commands to ensure order in the cosmos. The pharaoh, as in other cultures, also performed rituals that re-enacted the creation of the world. He, too, was expected to conquer death and play out the entire cosmic drama and to set all things in order again for his earthly reign which was considered a metaphor for a new creation.

In Mesoamerica, we have a slightly different picture, which in part is like that of Israel and Sumeria, but, in fact, is much closer to Egyptian traditions. In recent years, Mesoamerican scholars have been deciphering hieroglyphic texts that describe royal genealogy and interpreting iconography. The iconography is their art, which is very symbolic. They tell us much about royalty in this part of the world. For example, Joyce Marcus tells us that, “By maintaining the belief that as a group they had enjoyed a separate, divine descent, Maya royalty remained the only individuals who could serve as mediators between the secular commoners, on the one hand, and the divine supernaturals . . . on the other.” The Maya, in particular, went to great lengths to establish their divine ancestral connections. Chan-Bahlum, for example, who was the son of the great king Pacal of Palenque, in Chiapas, Mexico, falsified his genealogy. Scholars have determined that this was done to reflect his ancestral genealogy back to the founder of the dynasty, and from that point back to the gods of creation. Consequently, both Pacal and Chan-Bahlum were considered offspring of divinity. Their eventual godhood was now established without question in the historical records of Palenque. We should note that according to Jewish tradition, a new king symbolically became, when anointed, a son of God. Because the Maya king was the descendant of divine royalty, he became a special messenger of the gods, which is comparable to the function of the kings in the Middle East. It has been well-established that the kings performed sacrifice on behalf of their people. This was another facet of kingship that was unprecedented in both Mesoamerica and the Near East.

In the Near East, the cosmos and man were thought to be periodically regenerated through sacrifice. This could be done through a vicarious sacrifice, where an unblemished animal, a human victim, or a burnt offering was used as a substitute for the king. We all know the purpose of sacrifice, and that it was to be in similitude of our Lord’s sacrifice for us; but anciently, the people performed this practice without understanding the real reason behind the symbolism of sacrifice and the future Atonement. Types and shadows appear throughout these traditions.

The substitute king is of special interest here, especially in the Middle East, for it was thought that a captive died vicariously for the king, in order that both the king and the people might live. For example, in the Egyptian Sed Festival, a substitute king was sacrificed, followed by a symbolic resurrection of the king. This rebirth became a realization in the eyes of the Egyptians when the king mounted his throne as the ruler for a new number of years. The same ideology was also held in Mesoamerica. Sacrifice could be in the form of burnt offerings, blood-letting by kings, which was a form of self-sacrifice, or the sacrifice of human victims – the more royal, the better. Now let me explain where this comes from, because what the Maya king did here was to recreate certain events in the creation mythology as recorded in the Popul Vuh. The Popul Vuh was written by the Quiche Maya of Guatemala in post-conquest times. This oral history was passed down from one generation to the next for hundreds of years. In fact, mythology from the Popul Vuh goes back to illustrations on stelae at Izapa, from around 200 B.C., and perhaps even back to Olmec times.

The creation story in the Popul Vuh revolves around two brothers, Hunahpu and Xbalanque, simply referred to as the hero-twins. The hero-twins, we must note, were ball players. The objective of the hero-twins was to defeat the lords of death and chaos in the underworld. This is an event that took place before the day of creation; before all things were set in order. To accomplish this task it was necessary for the hero-twins to allow themselves to be sacrificed. And, because they had divine powers, they were in the end resurrected. Maya kings, therefore, re-enacted the role of the hero-twins, and by doing so brought a renewal of prosperity and order into their kingdom. Sacrificial victims were substituted for the king in his role as one of the Popul Vuh’s hero-twins. When the hero-twin, Hunahpu lost his head in the underworld, it was comparable to the loser who would lose his head in a real ball game played by the Maya.

The substitute sacrifice theme can also be seen in Piedras Negras, Guatemala, where late-Classic rulers are portrayed climbing a scaffold as they became enthroned. On one stela, the victim lies at the bottom of the scene. On this particular stela, the king, bloody footed from the sacrifice of the victim, climbs to the niche, which is the cubby-hole at the top, surrounded by symbols of the sky and identified as the heavenly realm. The king sits comfortably upon a pillow in front of the niche. The victim on this stela was sacrificed vicariously for the king. And, along with the Popol Vuh hero-twin who died, and defeated the lords of death in the underworld, the king rises victoriously to his celestial throne as a resurrected deity.

Substitute sacrifice had similar implications among the Aztecs. At certain festivals of renewal, a handsome youth who was in perfect health and without blemish was lavished upon for a year and given privileges of royalty, educated, and even considered a god. As a substitute for a royal sacrifice, he was then killed and thrown down the stairs of the temple. Then, when the king came out of his temple, he appeared as though he had died and was reborn.

.jpeg)

This slide is a roll-out from a Mesopotamian cylinder seal. The king also played the role of guardian of nature for the benefit of the people. In other words, if he could ensure there would be rain to bring good crops, his people survived. And, if he protected his people from their enemies, his people survived. If he was chosen as the one to be in direct communication with the gods, he had the gods’ approval, and as a result his people survived. So the king was the guardian supreme of his people, just as the first man on the earth was the gardener and guardian of all he surveyed. On this roll-out seal, you can see the king in duplicate next to the sacred Tree of Life. The author of the book, The King and the Tree of Life in the Ancient Near Eastern Religions, reports that in the Near East, the king was actually given the name of ‘gardener,’ which was considered to be a sacred title. Throughout much of the art of Mesopotamia are seen images of the king guarding the Tree of Life, which symbolized not only the king’s service to the gods, but that he was the mediator and had the gods’ blessings. In many scenes from the Middle East, the king is shown holding a scepter bearing leaves, branches, or flowers. According to some scholars, this was a twig from the Paradise Tree, which in the origin of the creation had been borne by Adam himself, who had cut a branch from this tree. One Near Eastern specialist points out the tradition that Adam, and the kings who came after him, carried this life-giving branch from the Tree of Life in their role as “Gardener.” In Mesoamerica we find the same theme of the gardener king. Among the Aztecs every year, a one-day ceremonial tilling of the land was performed by the king. The tilling was performed in maize fields, and maize is one of the forms of the World Tree, the Tree of Life. We can even go back to the early Olmec civilization and see that it was coming from them, for gods to hold vegetation from the World Tree. Perhaps the scenario of the king as gardener would go like this: the first man was a gardener in paradise and was responsible for taking care of his garden as instructed by his god. He was the first of his race. He was the head of his branch; he could even be considered the trunk of the genealogical tree of the human race. This was also true of Near Eastern kings. In the king’s role as the gardener who tends the Tree of Life, John Gray wrote, “We have surely the original of primordial man, the Hebrew Adam -- the image of God in the Garden of Eden with its Tree of Life.”

Among the Maya, the king often wore the costume of the maize god, who is referred to by Mayanists as First Father. To the Maya, First Father was the progenitor of the human race. It has already been established that the king was the guardian of ordered nature, especially in the context of the World Tree. When the Maya king dressed as First Father, he demonstrated his association with the first man who has strong agricultural ties. It has been written of the Maya, that the ruler was the axis that connected the heavens to the underworld. In the Middle East we have the same concept. In ancient times, royal cities were considered the image of the cosmos, while the king was the axis mundi . The most profound thing that I have found in this study is that the king was considered the World Tree, the Tree of Life, the center of the world. This unique concept was held in both Mesoamerica and the Middle East.

The Sumerians in Mesopotamia depicted the Tree of Life as a god named Tammuz who is mentioned in Ezekiel 8:14. Tammuz was associated with the underworld and was an ever-dying, ever-resurrecting god. There are many pagan idols that were types and shadows of the deity who would die and be resurrected, but they didn’t understand the true meaning of this event. In Sumerian literature, Tammuz was sometimes called a shepherd and/or a gardener, and was repeatedly held as a cedar, which was his cult tree and the symbol of this deity. In Mesopotamia, the king was often referred to as a cedar, and at times would proclaim himself to be the Tree of Life. In the Near East the king might be viewed as being, himself, a twig taken from the Tree of Life.

Now, we will turn our attention to Egypt. First of all, the god Osiris was also known as the “Great Sky Tree.”

.jpeg)

The Egyptian grain god, Osiris, was decapitated and dismembered by his arch enemy, Seth, the god of death. Some of his body parts were placed in a tree from which he was subsequently reborn. In the Mayan Popul Vuh, the grain god, who is the father of the hero-twins, was decapitated by the lords of death, and his head hung in a tree. The important thing here is that the symbol of Osiris is a djed. A djed is a pillar with a statue of Osiris with four bars across it. It has been interpreted both as a tree and as the backbone of Osiris. The djed was originally considered to be the bound sheaf of the first grain of the harvest. The Egyptian king used the symbol of the djed to portray stability and his life in the kingdom.

As for grain in Mesoamerica, it, too, was sometimes portrayed as the World Tree. In the Temple of the Foliated Cross in Palenque, a maize plant is considered to be the Tree of Life. In Mesoamerica we find the same meaning for ‘king’ as those of the Middle East; that the World Tree, the axis of the earth, was materialized in the person of the king. Being a representative of the Tree of Life or World Tree became one of the titles of the Maya kings, where they were often designated by a certain glyph. The king actually personified the Tree in the flesh. It’s to the Olmec, the earliest civilization that we can turn to look for the root of this tradition. In Mesoamerica, the Olmec were the first to associate the Tree with the reigning ruler. A pictorial from Dumbarton Oaks shows an Olmec ruler who wears atop his head the personified World Tree. It actually has a little face to it. Later, the Maya had a similar headdress on a ruler from Kaminaljuyú, which some scholars propose to be the city of Nephi. It has a bigger branch of the Tree of Life, with big leaves on it. Sometimes a Maya ruler would wear the whole regalia of the World Tree.

We’re now going to discuss in reverse and show that the World Tree has the same attributes as the king. Some of the earliest representations of the Tree of Life in Mesoamerica, as the axis of the earth, were made by the Olmecs. An inscribed stone tablet from Ahuelican, Guerrero, Mexico, illustrates many of these things. There is an ‘x’ at the top. The ‘x’ stands as the center of the sky. Around it is an arc of 13 squared, round scallops, which may represent the 13 heavens, because they thought in Mesoamerica that there were 13 heavens. Under the sky sign there is a tree touching its branches to the top (the heavens), and down into the next element. The element is a temple pyramid that represents the sacred mountain of creation. Under that we have a cave, which represents the underworld where everyone returns after death, and then resurrect. These interpretations are not just mine, but they also come from archaeologists.

Throughout the Middle East, festivals were performed that involved the hoisting up of the tree, which symbolized the Tree of Life at the time of creation. For example, there was a New Year ceremony in Egypt involving the raising of the djed pillar with the four branches across it. This is what the king did at the time of his accession or the time of his reinstatement to the throne. The people would grab hold of the ropes coming from the top and walk around it maypole-style. This is similar to the maypole ceremonies in Europe, which still go on today; in fact, in Austria there are may-poles all over the place. By going around the maypole it’s as though they participate in the creation of the earth. It’s bringing renewal; it’s bringing resurrection when all things spring forth in the spring. So the maypole concept actually started in Egypt. In Mesoamerica, the natives still perform the ceremonies where ropes extend down from a platform on top of a pole. The pole represents the axis of the earth. No matter what town you go into Middle America, that is their center.

The Maya kings were the guardians of the World Tree. They wore an apron of the World Tree. It had a face on it, because they believe that all things have spirits in them, so the tree was alive. The king is the Tree of Life to his community. On one side of his apron are branches, which represent the branches of the Tree. The apron with branches on it holds special significance in LDS temple worship.

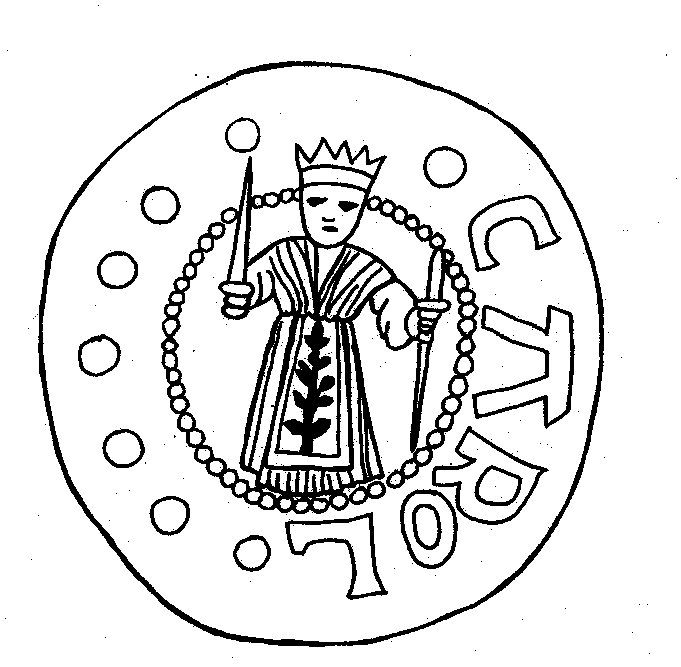

Even Charlemagne, who reigned in the 8th century A.D., wore an apron with the Tree of Life on it. So, we have it in both worlds: we have it in Mesoamerica and we have it in the Near East – the same concept. In Mesopotamian art, you often see trees with a bird at the top. You see the same things in Mesoamerica. Many scenes show a tree with a bird on top of it.

Many of you are familiar with the sarcophagus lid of king Pacal in Palenque. It is a magnificent sarcophagus lid. Pacal died at around 80 years of age. He is portrayed as the young maize god, who is First Father. As he falls into the jaws of the underworld, he rises up with the Tree of Life springing from his chest. This is his resurrection. The image of Pacal has branches hanging down, the Tree of Life with a face on it, and he has long quetzal feathers in his headdress. This is a wonderful sarcophagus lid. Pacal is in the position when people are being reborn, or even when children are being born. So, here, he is being resurrected with the Tree of Life coming from his chest, and with the bird element at the top.

The people of the Book of Mormon had knowledge and traditions from the Middle East. There are many scholars who are trying to pave the way to a better understanding of the possibility of sea voyages to the New World.

Through prayer, we know the Book of Mormon is true. LDS scholars look to research as a missionary tool to bring others to consider the possibility that these things are true, and hopefully get them to look into these new insights that support the Book of Mormon. Most scholars specialize in just one part of the world and don’t afford themselves the opportunity to compare traditions of a culture they understand with other cultures in the world. So, what I’ve done is to try to show both sides and the similarities that are there. These similarities provide a persuasive argument for the Middle Eastern origin of many Mesoamerican peoples.