Civilizations Lost and Found: Fabricating History - Part Three: Real Messages in DNA

Civilizations Lost and Found: Fabricating History - Part Three: Real Messages in DNA

Deborah A. Bolnick, Kenneth L. Feder, Bradley T. Lepper, and Terry A. Barnhart

Volume 36.1, January/February 2012

The Lost Civilizations of North America documentary suggests that there is genetic evidence for a pre-Columbian migration of Israelites to the Americas. However, DNA studies provide no support for this hypothesis.

"DNA science apparently settles the biological question of who these ancient, advanced Hopewell mound builders were. But where else is this DNA found? And where did it originate?"—The Lost Civilizations of North America

In Part One of our series on diffusionist perspectives espoused in the Lost Civilizations of North America documentary (SI, September/October 2011), we discussed allegations made in the documentary that the true history of ancient North America has been hidden, perhaps intentionally, by mainstream scientists and historians (Feder et al. 2011). In Part Two (November/December 2011), we addressed claims made by diffusionists in general and in the documentary in particular concerning the discovery of artifacts with written inscriptions presented in support of that alternative history (Lepper et al. 2011). Here, in Part 3, we will address the interpretation proffered by some of those interviewed in the documentary that DNA studies prove a direct biological and historical connection between the mound builders of the American Midwest and the ancient inhabitants of the Middle East.

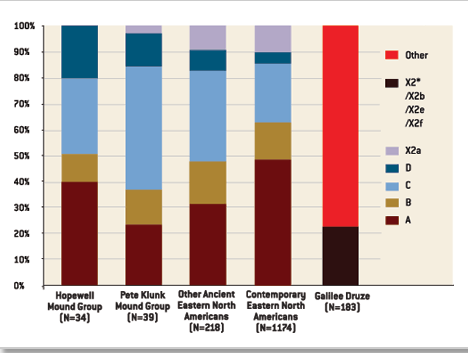

Lost Civilizations: Genetic Evidence

DNA studies have helped to address important questions about the biological makeup of Hopewell mound builder populations and where their ancestors came from, but the genetic data do not provide any evidence for a direct link between the Hopewell and Israelite populations of the Middle East, as some interviewees in Lost Civilizations claim. To date, DNA has been extracted from the remains of seventy-three individuals buried at two sites exhibiting Hopewell archaeological features (the pete Klunk mound group in Illinois and the Hopewell mound group in Ohio). Maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) was analyzed, and it shows that the genetic makeup of these populations was broadly similar to other ancient and contemporary Native American populations from eastern North America (Mills 2003; Bolnick and Smith 2007) (Figure 1). When the Hopewell population (as well as other Native Americans) is compared with Old World populations, they are most genetically similar to populations in Asia. The scientific consensus, based on more than 150 studies of Native American genetic variation, suggests that all Native Americans are descended from a single source population that originated in Asia and migrated to the Americas via Beringia (Figure 2) approximately fourteen thousand to twenty thousand years ago (Kemp and Schurr 2010). This consensus reflects not only the observed patterns of mtDNA variation but also studies of paternally inherited Y-chromosome markers and biparentally inherited autosomal markers.

Figure 1. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroup frequencies for Native American populations from eastern North America and the Galilee Druze. Note the level of consistency in the distribution of mitochondrial haplogroups among Native Americans. The distribution of haplogroups in a Galilee Druze population is quite different.

Figure 1. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroup frequencies for Native American populations from eastern North America and the Galilee Druze. Note the level of consistency in the distribution of mitochondrial haplogroups among Native Americans. The distribution of haplogroups in a Galilee Druze population is quite different.

While the Lost Civilizations video does mention this "mainstream" perspective, it emphasizes a different interpretation of the Hopewell genetic data. Specifically, the video suggests that the presence of a mtDNA lineage known as "haplogroup X" in the Hopewell population is evidence of a pre-Columbian migration of Israelites to the Americas because haplogroup X originated in the "hills of Galilee" in Israel and began to disperse out of the Middle East approximately two thousand years ago. This argument is seriously flawed for four reasons.

First, while several genetic studies indicate that haplogroup X may have first evolved in the Near East (Brown et al. 1998; Reidla et al. 2003; Shlush et al. 2008), these studies do not suggest that it originated specifically in Israelite or other Hebrew-speaking populations. Haplogroup X is found throughout the Near East, western Eurasia, and northern Africa, and it is not unique to (nor especially common in) Israelite or Jewish populations (Reidla et al. 2003; Behar et al. 2004). Shlush et al. (2008) did find a higher frequency of haplogroup X in the Galilee Druze, a (non-Jewish) population isolate that practices a distinctive monotheistic religion, but the authors themselves point out that their nonrandom sampling strategy does not provide an accurate estimate of population haplogroup frequencies. Furthermore, Shlush et al. (2008) argue that the Galilee Druze represent a contemporary "refugium" for haplogroup X, not that haplogroup X must have originated in the hills of Galilee (as diffusionist Donald Yates claims in the video).

Figure 2. This map shows the configuration of the modern coastlines of northeast Asia and northwest North America, along with the maximum Late Pleistocene extent of the Bering Land Bridge. Its existence, between thirty-five thousand and eleven thousand years ago, provided a broad avenue across which human beings first entered the New World from the Old.

Second, and more important, the forms of haplogroup X found in the Galilee Druze (and elsewhere in the Near East) are not closely related to the particular form of haplogroup X found in Native Americans. All members of haplogroup X share some mutations, reflecting descent from a common maternal ancestor, but other mutations divide haplogroup X mtDNAs into various subdivisions (subhaplogroups) that diverged after the time of the shared maternal ancestor (Reidla et al. 2003). The Hopewell and other Native American populations exhibit sub-haplogroup X2a, which is different from the subhaplogroups present in the Galilee Druze (subhaplogroups X2*, X2b, X2e, X2f) or other Middle Eastern populations (Reidla et al. 2003; Shlush et al. 2008; Kemp and Schurr 2010). Because subhaplogroup X2a is not found in the Middle East and is not particularly closely related to the forms of haplogroup X that are found in that region, the haplogroup X data do not provide any evidence for a close biological relationship between Hopewell and Middle Eastern populations or any support for a direct migration from the Middle East to the Americas in pre-Columbian times.

Second, and more important, the forms of haplogroup X found in the Galilee Druze (and elsewhere in the Near East) are not closely related to the particular form of haplogroup X found in Native Americans. All members of haplogroup X share some mutations, reflecting descent from a common maternal ancestor, but other mutations divide haplogroup X mtDNAs into various subdivisions (subhaplogroups) that diverged after the time of the shared maternal ancestor (Reidla et al. 2003). The Hopewell and other Native American populations exhibit sub-haplogroup X2a, which is different from the subhaplogroups present in the Galilee Druze (subhaplogroups X2*, X2b, X2e, X2f) or other Middle Eastern populations (Reidla et al. 2003; Shlush et al. 2008; Kemp and Schurr 2010). Because subhaplogroup X2a is not found in the Middle East and is not particularly closely related to the forms of haplogroup X that are found in that region, the haplogroup X data do not provide any evidence for a close biological relationship between Hopewell and Middle Eastern populations or any support for a direct migration from the Middle East to the Americas in pre-Columbian times.

Third, it is misleading and inappropriate to focus exclusively on haplogroup X and to ignore all other mtDNA lineages when considering the genetic origins of the Hopewell mound builders-especially since haplogroup X was found in only one of the seventy-three Hopewell individuals studied. As noted earlier, when all mtDNA haplogroups present in the Hopewell population (as well as other Native Americans) are considered, the genetic evidence clearly indicates an Asian origin. Furthermore, if there had been a pre-Columbian migration of Israelites to eastern North America, we would almost certainly see other common Middle Eastern lineages in the Hopewell and other Native American populations. We don't. None of the thirteen other mtDNA haplogroups found in the Galilee Druze is present in the Hopewell or other pre-Columbian Native Americans (see Figure 1). Nor do we see any of the common Druze or Middle Eastern Y-chromosome haplogroups in indigenous Americans. The genetic data therefore provide no evidence whatsoever for a migration of Israelites to eastern North America.

Finally, DNA studies do not suggest that haplogroup X began to disperse out of the Middle East only about 2,000 years ago, as diffusionist Rod Meldrum claims in the Lost Civilizations video. Meldrum argues that there is a scientific controversy over the rate of mtDNA mutation, and he suggests that (a) the most accurate mutation rate estimates come from human pedigree studies and (b) those mutation rates demonstrate that haplogroup X began to diversify and spread approximately two thousand years ago. However, the particular controversy that Meldrum cites is a decade old, concerns the mutation rate in only one small segment of mtDNA (the control region), and has generally been resolved. Pedigree studies measure the rate of mutation observed in parent-offspring comparisons, but many mutations are eliminated within a few generations of their occurrence because of natural selection, genetic drift, and recurrent mutation at some sites in the DNA. The measurable rate of mtDNA evolution therefore decreases over time (Soares et al. 2009), making it inappropriate to use mutation rate estimates from pedigree studies for dating the origin and diversification of most lineages (for example, any that originated more than a few generations ago). Instead, the mtDNA mutation rate is calculated by measuring the number of genetic differences between two or more individuals (or species) and then dividing that number by the length of time since they diverged from a common ancestor. The timing of their divergence is based on fossil, archaeological, and/or geological evidence, and it is not simply "theoretical" (as Meldrum suggests). Furthermore, Meldrum does not rely on newer findings to argue that haplogroup X began to diversify and spread only two thousand years ago, as he claims, but rather on an old and unusually fast estimate of the mtDNA mutation rate (Parsons et al. 1997). Virtually all pedigree studies have found significantly lower mutation rates (Howell et al. 2003) than the one Meldrum uses, which suggests that haplogroup X began diversifying much earlier than he claims. Studies of the complete mitochondrial genome (rather than just the control region), using less controversial mutation rates for the mtDNA coding region, also suggest that haplogroup X began to diversify much earlier (~31,800 years ago; Soares et al. 2009).

Conclusion

In the past, many scholars have pointed to a sometimes explicitly racist agenda behind the claims of diffusionists who argue that the glories of Native American civilizations were achieved only through borrowing from various Old World groups. The producers of the Lost Civilizations of North America and the diffusionists they feature in their documentary turn this argument on its head by suggesting that it is instead those “mainstream” scholars who are the real racists because they deny Native Americans their role in an already globalized world of the early centuries of the Common Era. However, the only support for this picture of Native American–Old World interactions two thousand years ago comes from resurrected frauds and distorted history. There is no credible archaeological or genetic evidence to suggest that any Old World peoples migrated to the Americas after the initial incursion from Siberia prior to the tentative forays of the Norse beginning at around 1000 CE other than limited contacts between Siberia and the American arctic.

References:

Behar, Doron M., Michael F. Hammer, Daniel Garrigan, et al. 2004. Mtdna evidence for a genetic bottleneck in the early history of the Ashkenazi Jewish population. European Journal of Human Genetics 12: 355-64.

Bolnick, Deborah A., and David G. Smith. 2007. Migration and social structure among the Hopewell: Evidence from ancient DNA. American Antiquity 72: 627-44.

Brown, Michael D., Seyed H. Hosseini, Antonio Torroni, et al. 1998. MtDNA haplogroup X: an ancient link between Europe/Western Asia and North America? American Journal of Human Genetics 63:1852-61.

Feder, Kenneth, Bradley T. Lepper, Terry A. Barnhart, and Deborah A. Bolnick. 2011. Civilizations lost and found: Fabricating history, part one: An alternate reality. Skeptical Inquirer 35(5) (September/October): 38-45.

Howell, Neil, Christy Bogolin Smejkal, D.A. Mackey, et al. 2003. The pedigree rate of sequence divergence in the human mitochondrial genome: There is a difference between phylogenetic and pedigree rates. American Journal of Human Genetics 72: 659-70.

Kemp, Brian M., and Theodore G. Schurr. 2010. Ancient and modern genetic variation in the Americas. In Human Variation in the Americas. Benjamin M. Auerbach, editor. Center for Archaeological Investigations, Occasional Paper No. 38: 12-50.

Lepper, Bradley T., Kenneth L. Feder, Terry A. Barnhart, and Deborah A. Bolnick. 2011. Civilizations lost and found: Fabricating history, part two: False messages in stone. Skeptical Inquirer 35(6) (November/December): 48-54.

Mills, Lisa. 2003. Mitochondrial DNA analysis of the Ohio Hopewell of the Hopewell Mound group. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.

Parsons, Thomas J., David S. Muniec, Kevin Sullivan, et al. 1997. A high observed substitution rate in the human mitochondrial DNA control region. Nature Genetics 15: 363-68.

Reidla, Maere, Toomas Kivisild, Ene Metspalu, et al. 2003. Origin and diffusion of mtDNA haplogroup X. American Journal of Human Genetics 73: 1178-90.

Shlush, Liran I., Doron M. Behar, Guennady Yudkovsky, et al. 2008. The Druze: A population genetic refugium of the Near East. PLoS ONE 3(5): e2105.

Soares, Pedro, Luca Ermini, Noel Thomson, et al. 2009. Correcting for purifying selection: An improved human mitochondrial molecular clock. American Journal of Human Genetics 84: 740-59.

Disclaimer

We are well aware that a claim underlying the Lost Civilizations documentary—that the mound-building people of the American Midwest were migrants from the Middle East 2,000 years ago—may be informed by religious doctrine. It is our position in this paper, however, that whatever inspires this claim is not nearly as important as the fact that it is plainly wrong. As such, we will leave it to others to assess the role played, if any, by religion in shaping Lost Civilizations and focus instead on scientific evidence relevant to that claim.

Deborah A. Bolnick, Kenneth L. Feder, Bradley T. Lepper, and Terry A. Barnhart

Deborah A. Bolnick is assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin.

Kenneth L. Feder is professor of anthropology at Central Connecticut State University. He is a fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry.

Bradley T. Lepper is the curator of archaeology for the Ohio Historical Society in Columbus, Ohio.

Terry A. Barnhart is professor of history at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, Illinois.