“The Waters of Sidon”: The Grijalva River or the Usumacinta River?

Copyright © 2009 Joseph Lovell Allen, Blake Joseph Allen, and Ted Dee Stoddard

|

According to Lawrence L. Poulsen, retired University of Texas research biochemist, “Using the three dimensional satellite maps incorporated into the computer program ‘EARTHA Global Explorer DVD’ by Delorme, [we can make] a thorough search of the geography of America in 3D. . . . Such a search results in one and only one location that fits the geographic restraints imposed by the text of Alma 22:27 for the river Sidon. This [search supports] the Grijalva River, indicating that the Grijalva is the same river described as the Sidon in the Book of Mormon and as has been proposed by many proponents of Book of Mormon geographies.”1 We are three of the proponents whose analyses lead to the conclusion that the Grijalva River, which runs through the central depression of Chiapas, Mexico, is the river Sidon of the Book of Mormon. We invite all Book of Mormon readers to evaluate this article’s evidence and either accept it at face value or prepare valid rebuttals. |

The only defensible way to determine the New World setting for the Book of Mormon is to use the Book of Mormon itself in identifying relevant criteria that are generic in nature and that can be tested in connection with any proposed New World setting. An examination of the Book of Mormon for the purpose of determining such criteria that can apply anywhere yields the following critical criteria:

1. The area must show evidence of a high-level written language that was in use during the Book of Mormon time period for the Nephites, Lamanites, and Mulekites.

2. The area must reflect two high civilizations that show extensive evidence of major population centers, continual shifts in population demographics, extensive trading among the cultures, and almost constant warfare among the inhabitants—in harmony with the dates given in the Book of Mormon.

3. The archaeological dating of the proposed area must reflect thorough analyses of sites and artifacts with resulting radiocarbon dates that agree with the dates given in the Book of Mormon.

4. The historical evidence from the area must provide valid findings that dovetail with the customs and traditions associated with the peoples and dates of the Book of Mormon.

5. The geographic configuration of the area must resemble an hourglass as a reflection of two land masses and a narrow neck of land (an isthmus) dividing the two. The hourglass must be on its side in a horizontal position to justify the Nephite cardinal directions of “northward” and “southward” associated with the two land masses.

This article’s purpose is not to test those criteria against all possible New World Book of Mormon settings to determine which setting is valid. When objective Book of Mormon scholars do test those criteria, they discover that Mesoamerica—and only Mesoamerica—satisfies all five criteria. Therefore, without any equivocation, scholars can say that all New World events of the Book of Mormon, except Moroni’s journey to bury the golden plates in a hill in upstate New York, took place in Mesoamerica. That statement is neither a hypothesis nor a theory. The archaeological and historical records from Mesoamerica, especially for the past forty years, so overwhelmingly support the statement that the overall issue of location should be looked at as finalized. Thus, when Book of Mormon scholars and readers put all personal preferences aside and examine Mesoamerica from the perspective of the five criteria, the only totally objective conclusion that can be drawn is that Mesoamerica is, indeed, the New World setting for the Book of Mormon.

For relevancy purposes, no criterion among the five is associated with any specific geographic location in Mesoamerica. That is, contrary to the procedures followed by some Book of Mormon scholars, no one should attempt to identify proposed geographic sites, such as the river Sidon or the hill Cumorah, and then force Mormon’s map to fit those proposed sites. On the other hand, based on the fact that Mesoamerica is the New World setting for the Book of Mormon, we can then look at Mesoamerica’s geography, topography, mountains, wilderness areas, rivers and other bodies of water, valleys and hills, lowlands, highlands, other elevations, distances, archaeological sites, and so forth to determine whether they individually and collectively fit Mormon’s map as found in the Book of Mormon. Thus, Book of Mormon scholars who identify specific geographic locations in the Book of Mormon and then try to find a New World match for those locations get the cart before the horse. They should first apply the criteria to find the New World setting and then look for specific locations in that setting.

The comments that follow are an outcome of those procedures and are based on the following premises:

1. Mesoamerica is the New World setting for the Book of Mormon.

2. The narrow neck of land is the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

3. The land northward is the territory to the west and northward of Tehuantepec

4. The land southward is the territory to the east and southward of Tehuantepec.

5. The Jaredite civilization is equated with the Olmec civilization, whose territory was west of, northward of, and adjacent to the top of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.2

With the above discussion as a background, we are now ready in this article to determine the location of the river Sidon, which must be found somewhere in Mesoamerica. For the past few decades, scholars who have attempted to locate the river Sidon in Mesoamerica are about evenly divided in choosing either the Grijalva River or the Usumacinta River as the river Sidon, but our observations are that many scholars use subjective analyses, illogical reasoning, or a lack of adequate criteria in choosing between the Grijalva or the Usumacinta as the river Sidon. From our perspective, the task of deciding whether the Grijalva or the Usumacinta is Sidon should be a relatively simple one if we examine carefully what the Book of Mormon itself says and use that information in conjunction with archaeological and historical data from Mesoamerica. In the process, we must be totally objective in examining the data and drawing valid conclusions.

We conclude unequivocally that the Grijalva River is the river Sidon. The data that support that conclusion follow.

The Wilderness of Hermounts and the Land-Southward Game Preserve

One obscure but important warfare incident in the Book of Mormon gives us a clear indication that the Grijalva River is the river Sidon. That incident happened in connection with the wilderness of Hermounts. The Book of Mormon contains only one usage of the name “Hermounts,” and the overall story associated with the wilderness of Hermounts is reflected in the chapter heading of Alma 2: “Amlici seeks to be king and is rejected by the voice of the people—His followers make him king—The Amlicites make war on the Nephites and are defeated—The Lamanites and Amlicites join forces and are defeated—Alma slays Amlici.”

Mormon recounts the Hermounts story as follows:

And it came to pass that the people of Nephi took their tents, and departed out of the valley of Gideon towards their city, which was the city of Zarahemla.

And behold, as they were crossing the river Sidon, the Lamanites and the Amlicites, being as numerous almost, as it were, as the sands of the sea, came upon them to destroy them.

Nevertheless, the Nephites being strengthened by the hand of the Lord, having prayed mightily to him that he would deliver them out of the hands of their enemies, therefore the Lord did hear their cries, and did strengthen them, and the Lamanites and the Amlicites did fall before them.

And it came to pass that Alma fought with Amlici with the sword, face to face; and they did contend mightily, one with another.

And it came to pass that Alma, being a man of God, being exercised with much faith, cried, saying: O Lord, have mercy and spare my life, that I may be an instrument in thy hands to save and preserve this people.

Now when Alma had said these words he contended again with Amlici; and he was strengthened, insomuch that he slew Amlici with the sword.

And he also contended with the king of the Lamanites; but the king of the Lamanites fled back from before Alma and sent his guards to contend with Alma.

But Alma, with his guards, contended with the guards of the king of the Lamanites until he slew and drove them back.

And thus he cleared the ground, or rather the bank, which was on the west of the river Sidon, throwing the bodies of the Lamanites who had been slain into the waters of Sidon, that thereby his people might have room to cross and contend with the Lamanites and the Amlicites on the west side of the river Sidon.

And it came to pass that when they had all crossed the river Sidon that the Lamanites and the Amlicites began to flee before them, notwithstanding they were so numerous that they could not be numbered.

And they fled before the Nephites towards the wilderness which was west and north, away beyond the borders of the land; and the Nephites did pursue them with their might, and did slay them.

Yea, they were met on every hand, and slain and driven, until they were scattered on the west, and on the north, until they had reached the wilderness, which was called Hermounts; and it was that part of the wilderness which was infested by wild and ravenous beasts.

And it came to pass that many died in the wilderness of their wounds, and were devoured by those beasts and also the vultures of the air; and their bones have been found, and have been heaped up on the earth. (Alma 2:26–38; emphasis added)

Thus, the battle that preceded the routing of the Lamanites and Amlicites took place on the banks of the river Sidon in the land of Zarahemla. Mormon then makes the following points about the fleeing Lamanites and Amlicites:

• They fled from the land of Zarahemla and from the river Sidon toward the wilderness that was “west and north of Zarahemla.”

• The wilderness was “away beyond the borders of the land” of Zarahemla.

• The Lamanites and Amlicites were scattered on the west and on the north and eventually reached the wilderness that was called the wilderness of Hermounts.

• Hermounts was that part of the overall wilderness that was “infested by wild and ravenous beasts.”

• The bodies of the Lamanites and Amlicites who died in the wilderness were devoured by wild beasts and by vultures.

At issue here is whether we have any clues from the Book of Mormon or from Mesoamerican geography that would tell us where the wilderness of Hermounts is located. One given for purposes of this article is that Zarahemla was located either in the central depression of Chiapas in conjunction with the Grijalva River or somewhere along the Usumacinta River.

The process of determining whether the wilderness of Hermounts is associated with the Grijalva River or the Usumacinta River is rather simple when information from the Book of Mormon is combined with data from Mesoamerica. Simplistically, the river Sidon was relatively close to the wilderness of Hermounts, and the wilderness of Hermounts was west of the river Sidon. Therefore, to be the river Sidon, the Grijalva or the Usumacinta must be close to the wilderness of Hermounts and must permit the Lamanite/Amlicite and Nephite warriors to fight to the west of the river Sidon and then to the north into the wilderness of Hermounts.

At this point, we will assume that the conclusions of John L. Sorenson and others are correct in identifying the Grijalva as Sidon, the Chiapas central depression as the land of Zarahemla, and the site of Santa Rosa on the Grijalva as the city of Zarahemla. On a map of this geographic area, what will the answers be to two questions:

1. If we draw a line from Santa Rosa directly west, will we run into a wilderness area?

2. If we run into a wilderness area, will that wilderness area continue to the north if we make a ninety-degree angle with the line and continue drawing it to the north?

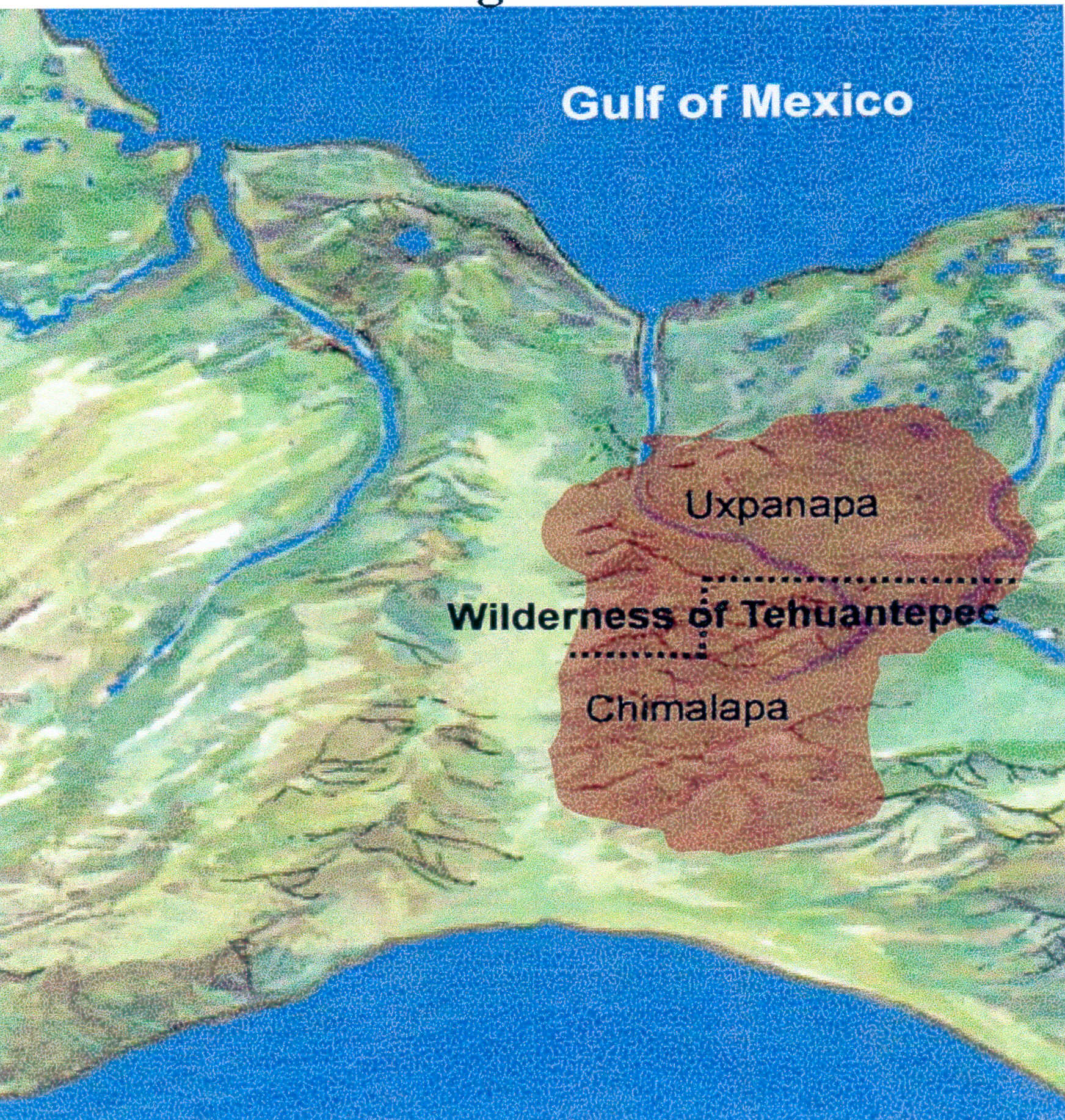

From the perspective of the Grijalva River, the answer to both questions is a resounding “Yes!” The wilderness area we run into is the Uxpanapa-Chimalapa wilderness (oosh pah NAH pah-chee mah LAH pah) with Chimalapa on the south and Uxpanapa on the north.

Before we discuss this wilderness area further, we will bring one other Book of Mormon historical point into the picture.

From the book of Ether, we learn the following:

And it came to pass that Lib also did that which was good in the sight of the Lord. And in the days of Lib the poisonous serpents were destroyed. Wherefore they did go into the land southward, to hunt food for the people of the land, for the land was covered with animals of the forest. And Lib also himself became a great hunter.

And they built a great city by the narrow neck of land, by the place where the sea divides the land.

And they did preserve the land southward for a wilderness, to get game. And the whole face of the land northward was covered with inhabitants. (Ether 10:19–21; emphasis added)

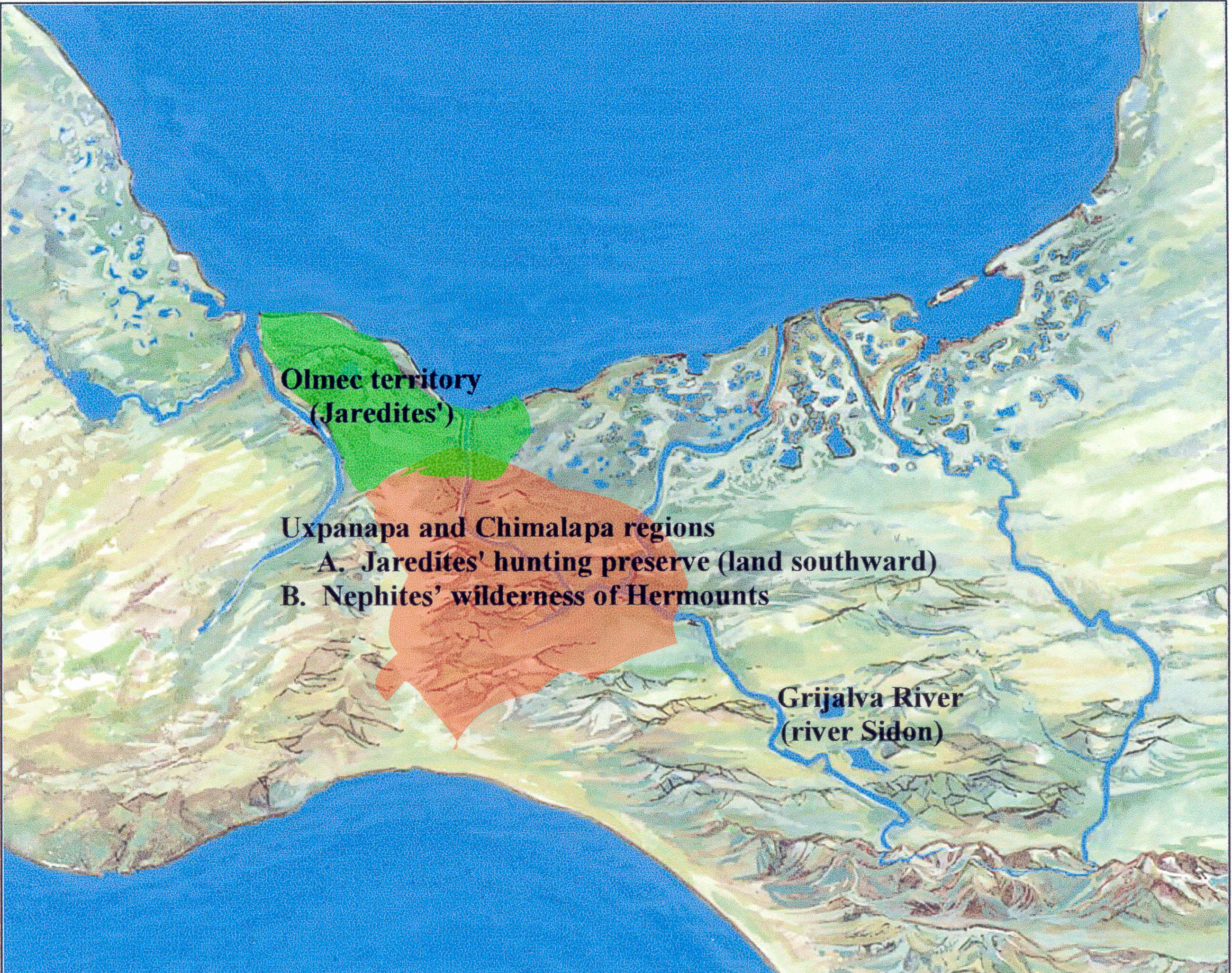

Thus, we know that the Jaredites never occupied the land southward but rather reserved it as a massive hunting preserve. And we know from the Olmec historical record that the Jaredites/Olmecs at one time or another lived on the north side of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, on both the west and the east. The Olmec record supports the Jaredite record’s statement that the Jaredites did not inhabit the territory east of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in the land southward but reserved it for a “hunting refuge.”

The geographic language of the Book of Mormon is descriptive enough that we should be able to locate the Jaredites’ “land southward for a wilderness, to get game” and the Nephites’ “wilderness, which was called Hermounts; and it was that part of the wilderness which was infested by wild and ravenous beasts.” The Jaredite record and the Nephite record are talking about the same geographic territory.

From a modern perspective, that territory is the Uxpanapa-Chimalapa region. It is contiguous to the southern half of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and thence east of the isthmus.

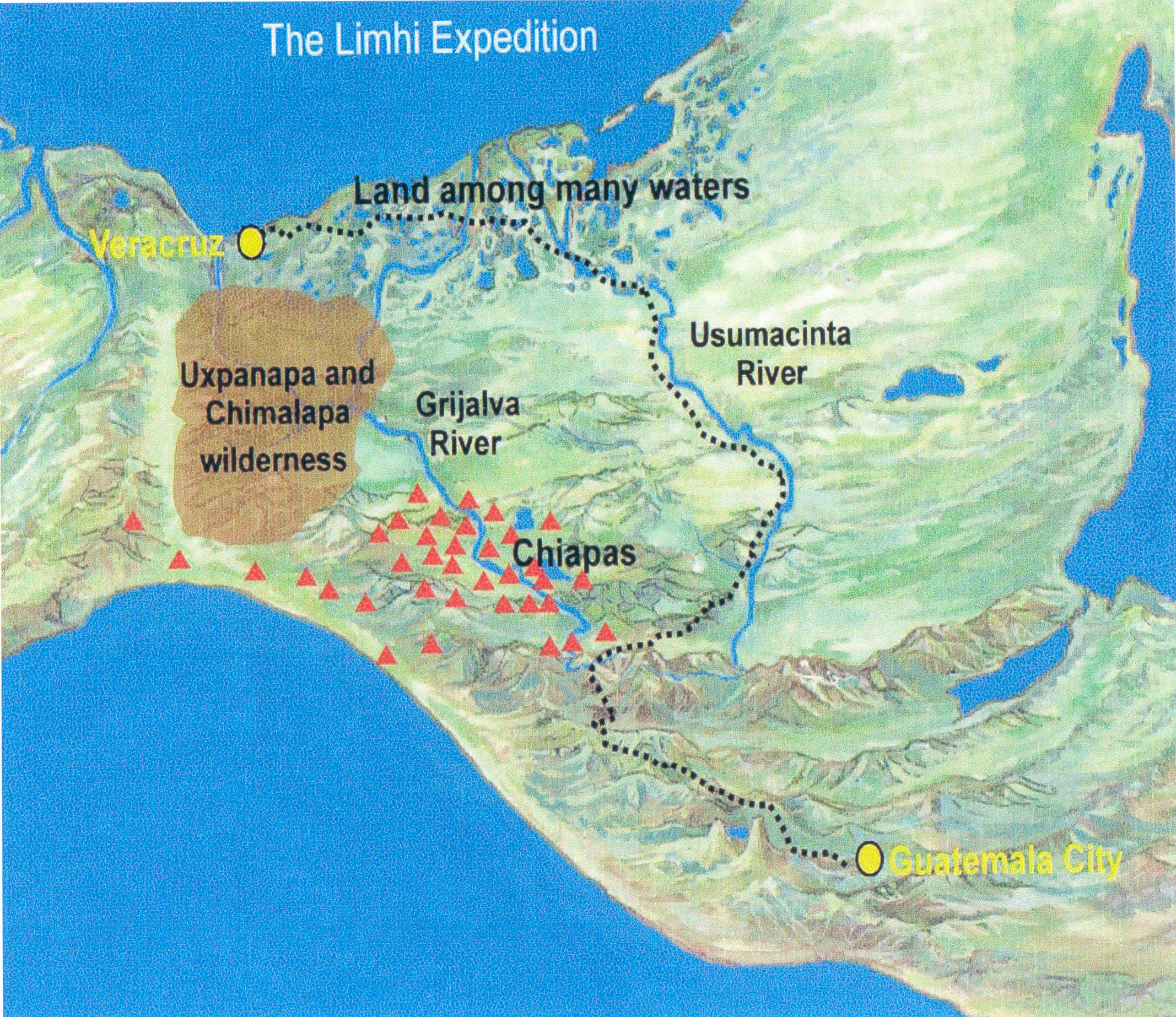

Figure 1. When we first go west from Santa Rosa on the Grijalva River and then go north from that point, we are in the middle of the Uxpanapa-Chimalapa wilderness area. The Uxpanapa-Chimalapa region is precisely in the correct location to be the Jaredites’ “land southward for a wilderness, to get game” and the Nephites’ “wilderness, which was called Hermounts.” This massive wilderness area has essentially been uninhabited throughout the history of Mesoamerica. Today, it is still almost uninhabited; but it continues to be home for many of the wild animals of Mexico. Indeed, it is a wilderness for “game” in the form of “wild and ravenous beasts.” (Log on to the satellite picture of this area, and then zoom in on this wilderness region; see http://www.maplandia.com/mexico/veracruz/.)

Based on the wording of Alma 2:36–37, if the archaeological site of Santa Rosa is the city of Zarahemla on the west bank of the river Sidon and if the Grijalva River is the river Sidon, then the Lamanites and Amlicites fled from the land of Zarahemla to the west and to the north to get to the Uxpanapa-Chimalapa region—the wilderness that was, indeed, “west and north of Zarahemla,” as figure 1 show

Figure 2. If John Sorenson and others are correct in identifying Santa Rosa as the city of Zarahemla on the west bank of the Grijalva River/Sidon, the direction to the wilderness area of Uxpanapa-Chimalapa and hence to the wilderness of Hermounts is “west and north of Zarahemla” as specified in Alma 2:36–37. In that respect, Uxpanapa-Chimalapa is “away beyond the borders of the land” of Zarahemla—just as the wilderness of Hermounts was “away beyond the borders of the land” of Zarah

As shown in figures 1 and 2, the region of Uxpanapa-Chimalapa meets all Book of Mormon requirements to be the Jaredites’ land southward that was preserved as a wilderness for hunting game and to be the Nephites’ wilderness of Hermounts that was part of “the wilderness which was infested by wild and ravenous beasts.” The correlations among the Jaredites’ hunting preserve, the Nephites’ wilderness of Hermounts, and today’s equivalent area known as the Uxpanapa-Chimalapa wilderness region are more than coincidence. Those correlations are based on our identification of the Grijalva River as the Book of Mormon’s river Sidon.

When we are looking for “wilderness” areas in Mesoamerica, we must look for forested, mountainous terrain or lowland jungle terrain—or perhaps both at the same time. When we are looking for the Jaredites’ land-southward hunting preserve and the Nephites’ wilderness of Hermounts, we are looking for potentially uninhabited territory as well as territory that is home to “animals of the forest,” “wild and ravenous beasts,” and even “vultures of the air.” One report describes the wilderness area of Uxpanapa-Chimalapa as follows:

The Uxpanapa-Chimalapa region covers c. 7700 km2 in extreme southeastern Veracruz and eastern Oaxaca states. The region includes the Atlantic slope of the eastern portion of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, mostly in the drainage of the Coatzacoalcos River and its major tributary the Uxpanapa River, and extends from the Gulf of Mexico lowlands southward to the highlands of the continental divide; a part of eastern Chimalapa is in the Grijalva River drainage. . . .

The Chimalapa area is notable for its very large tracts of undisturbed and little disturbed lowland and mountain forests; especially, there are large transects of undisturbed lowland rain forest to mountain cloud forest. The hill and riparian forests of Uxpanapa extend into the Chimalapa area. Hill forest is widespread in the lower Rio del Corte Valley and areas near the Sierra de Tres Picos and Sierra Atravesada. . . .

The region contains important timber resources. . . . The endemic species still include many that have never been investigated for possible uses, since the region was virtually uninhabited until the past few decades. . . .

The Uxpanapa-Chimalapa region is one of the most important remaining natural areas in Mexico for wild animals. There are large populations of such threatened species as jaguar and Baird’s tapir, together with spider monkeys, tayra, agouti, kinkajou and many others. . . .

Uxpanapa and Chimalapa form the headwaters of the Coatzacoalcos River drainage. . . .

The region has potential for tourism, especially with regard to the animals, the beautiful rock formations and flora of the karst zone, and the true wilderness quality of much of Chimalapa. . . .

Except for logging operations and other development near the Coatzacoalcos River in the west, [Uxpanapa] was almost completely undeveloped and unsettled until the early 1970s, when the federal government started a major project in the Veracruz portion of Uxpanapa to resettle indigenous Chinanteco people displaced by the Cerro de Oro dam. . . .

The history of the Chimalapa area has been quite different. Since pre-Hispanic times the Chima (a small Zoque population) have been there, centered in the area of the present town of Santa Maria Chimalapa.3

Can we identify any other wilderness area adjacent to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec that might be the Jaredites’ land-southward hunting preserve or the Nephites’ wilderness of Hermounts? Answer: No. Therefore, whether we lean toward the Grijalva or the Usumacinta as the river Sidon, the Uxpanapa-Chimalapa wilderness area is undoubtedly the Jaredites’ wilderness for hunting game and the Nephites’ wilderness of Hermounts.

When we realize the impact of discovering the role of the Uxpanapa-Chimalapa area as the Jaredites’ wilderness for hunting game and the Nephites’ wilderness of Hermounts, we need only examine a map showing the Grijalva and the Usumacinta in relation to Uxpanapa-Chimalapa to draw relevant conclusions about the river Sidon. In doing so, we will discover the following:

1. The distance due west from Santa Rosa on the Grijalva to Uxpanapa-Chimalapa is less than fifty miles—a very realistic distance for warring armies to cover in connection with the time available and the terrain of the area.

2. The distance due west from the Usumacinta River to Uxpanapa-Chimalapa is about 250 miles—a very unrealistic distance for warring armies to cover because of the time available and the almost impenetrable terrain west of the Usumacinta.

3. As explained in the next section, virtually no archaeological site of any consequence that dates to the first century BC can be located on the Usumacinta due east of Uxpanapa-Chimalapa.

4. Because of the geographic terrain between the Usumacinta and Uxpanapa-Chimalapa at this latitude, a warring faction could not have gone “due west” from the Usumacinta because of the mountainous terrain in that direction. To traverse the terrain, a marching army wanting to go west would have been required to make major north or south circuitous detours at many places long before the army reached Uxpanapa-Chimalapa and turned north.

5. If Uxpanapa-Chimalapa is the wilderness area of Ether 10:19–21 and Alma 2:37–38, the Usumacinta River cannot be the river Sidon. On the other hand, because of the location and nature of Uxpanapa-Chimalapa, the Grijalva River is clearly the logical candidate for the river Sidon.

Figure 3. The geographic terrain between the Grijalva and Uxpanapa-Chimalapa lends itself to a rapidly moving, westward-marching army. However, a westward-inclined marching army facing the geographic terrain between the Usumacinta and Uxpanapa-Chimalapa could not have gone due west because of the terrain and the population centers along the Grijalva.

Besides Uxpanapa-Chimalapa’s obvious geographic orientation in relation to the Grijalva River, two other Mesoamerica historical events tie Uxpanapa-Chimalapa to the Jaredites’ land-southward wilderness and the Nephites’ wilderness of Hermounts. Mormon tells his readers that many of the Lamanites/Amlicites died in Hermounts and “were devoured by [wild and ravenous] beasts and also the vultures of the air” (see Alma 2:38).

First, Uxpanapa-Chimalapa continues to be home to wild animals that can aptly be described as “wild and ravenous beasts.” Further, Uxpanapa-Chimalapa is an integral part of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. According to Meleseo Ortega Martinez, the word Tehuantepec is derived from the Nahuatl words tecuani and tepec. Tecuani reflects the meaning of “wild beast,” and tepec translates as “hill.” And according to the Nahuatl dictionary, tecuani also means “man-eating beast.” Thus, the composite outcome reflects the meaning of “hill of the fierce beasts” or “wilderness of wild beasts.”4 According to Lawrence L. Poulsen:

The almost exact correlation in meaning for Tehuantepec and Hermounts suggests that the wilderness of Tehuantepec is an ideal candidate for the Book of Mormon wilderness of Hermounts. A line drawn from this wilderness to the headwaters of the Grijalva River intersects with the Grijalva River near the ruins of Santa Rosa and never comes near the Usumacinta River except at its headwaters. The probable identification of Tehuantepec with Hermounts gives strong support to [the] identification of the Grijalva River as the Book of Mormon river Sidon.5

Second, Uxpanapa-Chimalapa is also nearby a national wildlife preserve named Biosfera de la Reserva del Ocote (Selva del Ocote), which means “forests of the vultures” and which has been set aside as a refuge for vultures of this region. And nearby is the city of Ocozocoautla, which means “land of vultures and serpents” in the Nahuatl language.

In summary, based on the geographic pointers given us in Ether 10:19–21 and Alma 2:37–38, we can easily resolve the river Sidon issue between the Grijalva and the Usumacinta by dealing with the following statement: Show me the Jaredites’ land-southward game preserve and the Nephites’ wilderness of Hermounts, and I’ll show you the river Sidon. Clearly, Uxpanapa-Chimalapa satisfies all criteria for the Jaredites’ land-southward wilderness area and the Nephites’ wilderness of Hermounts. Due east of Uxpanapa-Chimalapa is the Grijalva River in the Chiapas central depression. An obvious conclusion based on an examination of the Uxpanapa-Chimalapa and associated wilderness areas is the following: The Grijalva River is the river Sidon.

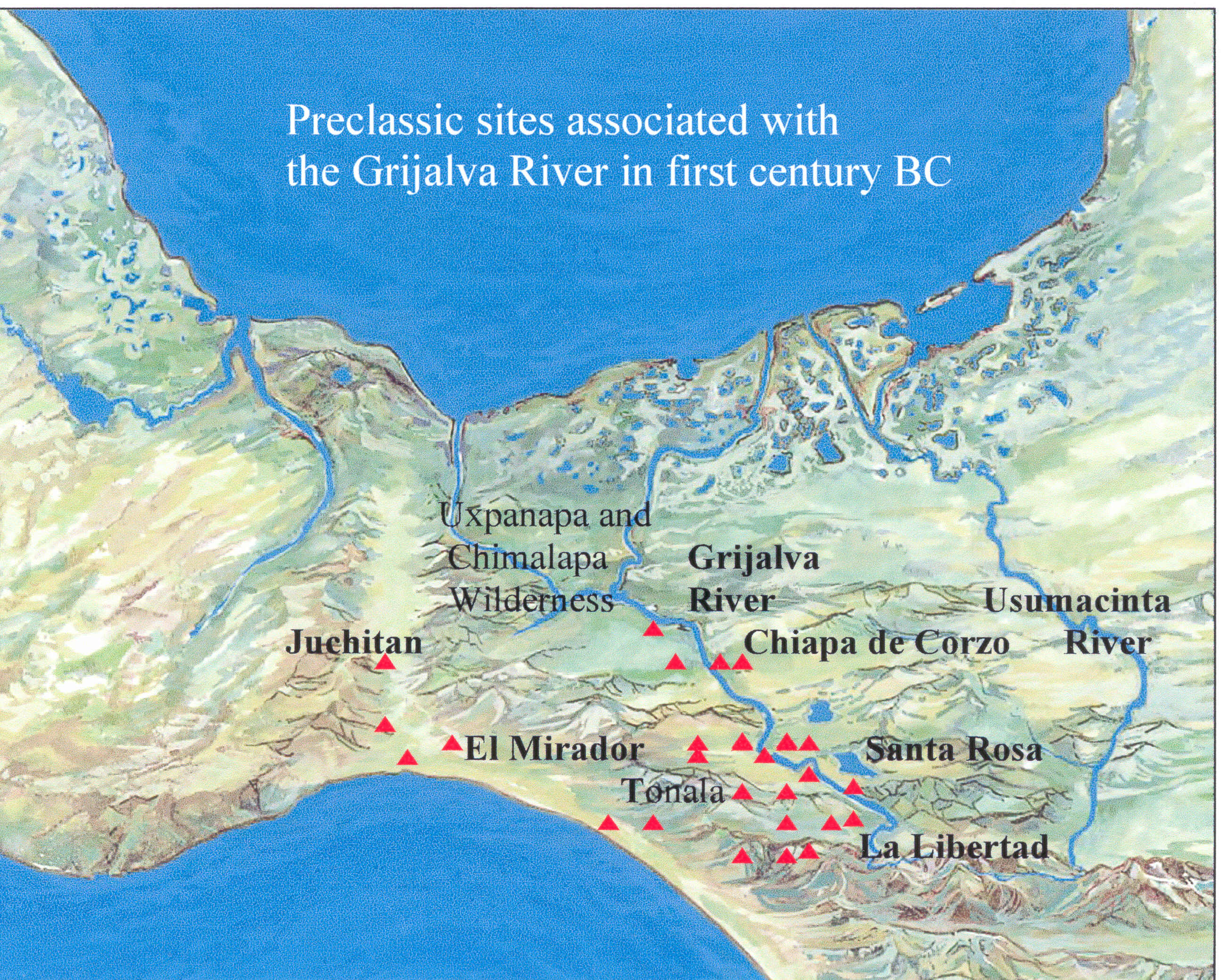

Preclassic Period Population Centers on the Usumacinta

Some tour directors mistakenly teach that the city of Zarahemla was located along the banks of the Usumacinta River. They do so, however, without authorization of archaeological evidence that dates from the fifth to second centuries BC—a strict requirement for any candidate to be the city of Zarahemla. That is, no sites of any consequence dating to the 500 BC to AD 250 time period have been documented along the Usumacinta River. Clearly, however, the Book of Mormon gives evidence of many cities of that time period associated with the city of Zarahemla.

The two most prominent sites along the Usumacinta are Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan, both of which are Maya Classic sites that were not founded until after AD 250—or toward the end of the history recorded in the Book of Mormon. They are located about twenty-five miles from each other, and they are about a hundred miles west of Tikal. They are approachable from Palenque when travelers drive to the Usumacinta River and take a launch upstream. They follow the same political and developmental pattern as the Classic Period ruins of Palenque, Calakmul, and Copan.

Piedras Negras is not a Book of Mormon city. Excavation work was initiated at Piedras Negras from 1931 to 1939 by the University Museum, University of Pennsylvania. Beginning in 1997, the site of Piedras Negras became part of a combined Guatemalan and American project led by Hector Escobedo and Stephen Houston, the latter formerly on the faculty of Brigham Young University but not a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Like Palenque and Copan, Piedras Negras may have been settled as a small village beginning at AD 250 to AD 300; however, the first ruler, who is simply labeled Ruler A, appears to have ascended to the throne around AD 460, which is 110 years from the time the Nephites had been exiled from the land of Zarahemla and the land southward. Piedras Negras is the largest site along the Usumacinta River. In its three-hundred-year post–Book of Mormon history, Piedras Negras was fraught with many wars. Its collapse also appears to be military in nature, coming directly from its neighbor to the south, Yaxchilan. After the fall of Piedras Negras in the eighth century AD, evidence shows that the Usumacinta continued as a major trade route for another century.

Thus, we see that the site of Piedras Negras did not begin until several hundred years after Mosiah and the Nephites moved in with the Mulekites in the city of Zarahemla on the banks of the river Sidon. That is, Piedras Negras did not even have a ruler until after the close of the Book of Mormon. Piedras Negras is not a Book of Mormon city!6

Like its neighbor Piedras Negras, Yaxchilan is a Maya Classic Period site whose dynasty began on July 23, AD 359, more than five hundred years after Mosiah traveled from Nephi to Zarahemla and became king over the land of Zarahemla. Yaxchilan did not exist as a structured city with a ruler until nine years after the Nephites were exiled from the land of Zarahemla. In other words, no Nephite ever lived at Yaxchilan.

Yaxchilan is situated in a horseshoe bend of the Usumacinta River, and although its dynasty describes an origin in the fourth century AD, most of what is seen today is the result of two eighth-century rulers who dominated its landscape. Yaxchilan is truly a magnificent Mesoamerica archaeological site, but tour directors who give the impression that the Nephites had something to do with the site are totally unethical or unknowledgeable—or both.

Just as no serious scholar of historical geography of the Book of Mormon today would consider Palenque, Uxmal, or El Tajin to be a Book of Mormon city, likewise, no reputable student of Mesoamerican history and geography would label Yaxchilan or Piedras Negras a Nephite site. Therefore, we must disqualify the Usumacinta River as a candidate for the river Sidon.7

In connection with the historical documentation of 200 BC to AD 200, the ancient document called The Title of the Lords of Totonicapan mentions that descendants of Abraham and Jacob went up the Grijalva and Usumacinta Rivers and settled along the frontiers of Chiapas and Guatemala. Although the Usumacinta River is mentioned, nothing in the document suggests that anyone settled along the Usumacinta—a fact that is verified by the lack of archaeological evidence.

Thus, population centers dating to the Late Preclassic Period (200 BC to AD 200), of the magnitude and location required by the Book of Mormon, have never been discovered along the Usumacinta River. For example, at 83 BC on the banks of the river Sidon, nineteen thousand soldiers were killed in a battle to gain control of the city of Zarahemla (see Alma 2:19). If they had been fighting on both sides of the Usumacinta, they would have been fighting to get control of a city that did not exist at that time!

We are not suggesting an entire absence of settlements along the Usumacinta in the first century BC. Small Preclassic settlements existed, as determined by pottery fragments that have been documented at Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, El Cayo, Fideo, Macabilero, El Kinel, La Tecnica, and Zancudero, all of which were located in close proximity to each other. At Zancudero, large defensive walls have been discovered that are apparently patterned after those at Becan and that date to the time period of Becan. Although Zancudero is not located specifically along the Usumacinta River, it is nearby. However, before we can legitimately label the Usumacinta as the river running through Zarahemla, we must look at two archaeological outcomes connected with the Usumacinta: (1) a wide pattern of abandonment of sites occurred in this region about AD 250 and (2) the sites were very sparsely populated.8

We should recall here that young Mormon visited Zarahemla at AD 322, seventy-two years after La Tecnica and Zancudero were abandoned. On that occasion, a war broke out in the borders of Zarahemla by the waters of Sidon. Thirty thousand Nephite soldiers were recruited to fight against the Lamanites (see Mormon 1:6–11). Therefore, we ask the following question: If no cities existed along the Usumacinta with a continual occupation from 500 BC to AD 322, why did the Nephites need thirty thousand soldiers for this battle? Further, at AD 331, a battle ensued that entailed forty-four thousand Lamanites and forty-two thousand Nephites. They were fighting somewhere—but they were not fighting in an attempt to capture the towns located in the Yaxchilan district of the Usumacinta River because, according to recent archaeological testing, those sites had already been abandoned.

In summary, when we look for population centers along the Usumacinta that correlate from a dating perspective with the Book of Mormon, we find essentially none along the Usumacinta. Therefore, population centers, as a singular criterion for choosing between the Grijalva and the Usumacinta as the river Sidon, clearly disqualify the Usumacinta and unconditionally qualify the Grijalva. Here is additional unequivocal evidence that the Grijalva River is the river Sidon.

Preclassic Population Centers on the Grijalva

On October 20, 1952, the New World Archaeological Foundation (NWAF) was incorporated in the state of California as a nonprofit, scientific, fact-finding organization. It originated as a result of discussions among Thomas Stuart Ferguson, Alfred V. Kidder of the Carnegie Institution, and Gordon Willey of Harvard University. Ferguson was an attorney and a member of the Church of Jesus Christ; Kidder and Willey were nonmembers and were professional archaeologists. The three of them collaborated in efforts to expand “the status of archaeology in Mexico and Central America.” Ferguson later commented on their efforts by noting: “It was unfortunate that so little work was being carried on in so important an area and that something should be done to increase explorations and excavations. . . . Despite the amazing discoveries made between 1930 and 1950, work on the Pre-Classic was virtually at a standstill in 1951. The result of the discussion was that we agreed to set up a new organization to be devoted to the Pre-Classic civilizations of Mexico and Central America—the earliest known high cultures of the New World.”9

The work of the NWAF is highly significant in helping readers of the Book of Mormon choose between the Grijalva River and Usumacinta River as the river Sidon. In fact, the issue should be resolved immediately in all readers’ minds if they were to visit the archaeological museum in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Chiapas, Mexico, and analyze the large Preclassic room map prepared by the NWAF.

As noted, one of the stated objectives of the NWAF was to concentrate on Preclassic Period sites in Mesoamerica (ca. 500 BC to AD 250). One of the NWAF maps shows Preclassic sites along both the Grijalva and Usumacinta Rivers. As explained in the previous section, the Usumacinta is noted for the absence of any major cities during the Preclassic Period—an outcome that is clearly reflected in the NWAF map. However, the NWAF documented more than fifty Preclassic cities along the Grijalva. Those facts alone should be enough to convince every reader of the Book of Mormon that the Grijalva River—not the Usumacinta River—is the river Sidon. That is, permanent cities were not built along the Usumacinta until after AD 250, so no amount of exploration along the Usumacinta will produce a suitable site for the city of Zarahemla, the primary Preclassic site on the river Sidon.

Figure 4. Map showing the presence of Preclassic sites on the Grijalva River from 300 BC to AD 250 along with the absence of Preclassic cities on the Usumacinta River during this period—according to the archaeological survey work of the New World Archaeological Foundation. As reflected in this map, the NWAF identified over fifty Preclassic sites in the Chapatengo-Chejel and upper tributaries subregions of the Chiapas central depression.10 The profusion of Preclassic Grijalva River sites and the lack of Preclassic Usumacinta River sites give clear evidence that the Grijalva—not the Usumacinta—is the Book of Mormon river Sidon.

According to Gareth W. Lowe, “The Central Chiapas region was plainly selected for investigation by the Foundation because some thought it the homeland mentioned in various legendary sources, and because of its central location between the more famed of the ancient American civilizations.”11 Following are general statements about the Chiapas central depression’s Grijalva River that lend support to its being the river Sidon:

1. The dominant city on the river Sidon in the land of Zarahemla was the city of Zarahemla. Unlike the Usumacinta, the Grijalva has an excellent candidate for the city of Zarahemla at the site of Santa Rosa. The NWAF did excavation work at Santa Rosa in 1956 and 1958. Today, Santa Rosa is inundated by waters backed up about seventy miles behind the Angostura Dam. “Santa Rosa became the largest, most significant ‘city’ in the Grijalva basin just at the time when Zarahemla is reported by the Book of Mormon as becoming a regional center.”12

2. Between 200 BC and 180 BC, Mosiah, who lived in the land of Nephi, led a righteous group of Nephites from the land of Nephi to the land of Zarahemla—where Mosiah discovered the people of Zarahemla (see Omni 1:12–19). When Zarahemla recounted orally his people’s history, he also recounted a portion of the history of the Jaredites. Zarahemla and his people had lived in the area of the Jaredites and had traveled into the south wilderness where Mosiah discovered them (see Alma 22:31). The people of Zarahemla and the people of Mosiah lived together in the city of Zarahemla, which we propose was the site of Santa Rosa.

However, the two groups probably continued to retain their individuality. For example, “Mosiah caused that all the people should be gathered together. Now there were not so many of the children of Nephi, or so many of those who were descendants of Nephi, as there were of the people of Zarahemla. . . . And now all of the people of Nephi were assembled together, and also all the people of Zarahemla, and they were gathered together in two bodies” (Mosiah 25:1–4; emphasis added).

As a reflection of this individuality in the area of Santa Rosa, “The cleavage of the valley into east and west cultural divisions is apparent on both an early and late level.”13 That “cleavage” was likely the result of both the Nephites and the Mulekites living in their individual geographic areas of Zarahemla. John L. Sorenson agrees:

A unique fact about the pattern of this settlement came to light in the excavations by the New World Archaeological Foundation. Archaeologist Donald Brockington, who helped excavate part of the largest pyramid mound in the center of Santa Rosa, found that in this structure, constructed in the first century BC, a layer of gravel had been laid which was then stuccoed over as a footing on which the mound was further built. The base gravel was of two completely different kinds, clearly brought there from two sources. The line separating the gravel areas was meticulously straight and was oriented approximately east and west, dividing the structure exactly in half. Furthermore, the site’s inhabitants lived in two oval-shaped zones separated from each other by a ceremonial zone oriented along this same line. Brockington concluded that the gravel had been laid down by two distinct social (perhaps linguistic) groups that occupied the site and that seem to have related to each other by formal ritual and political arrangements.14

3. Santa Rosa is in the proper direction and manifests the same elevation relationship to Guatemala, the logical candidate for the land of Nephi, as the city of Zarahemla does to the land of Nephi.

4. Santa Rosa is situated along the banks of the Grijalva River and is in close proximity to many other neighboring archaeological sites dating to the time period in which Zarahemla and its neighboring sites flourished.

5. The discovery of the Miraflores style and workmanship of pottery originating from Lake Atitlan, the logical candidate for the waters of Mormon, and Kaminaljuyu in Guatemala, the logical candidate for the city of Nephi, dating from the second century BC at Santa Rosa verifies an emigration relationship from the city of Nephi (Kaminaljuyu) and the waters of Mormon (Lake Atitlan) to the city of Zarahemla (Santa Rosa).

6. Period 3 of Santa Rosa was established as a prominent center in the Grijalva valley lasting from 500 BC to 100 BC. This time period corresponds to the arrival and settlement of the people of Zarahemla, the demise of the Jaredite civilization, and the arrival of Mosiah, who was made king over the land of Zarahemla.

7. Period 4 of Santa Rosa dates from 100 BC to AD 200, labeled as a period of efflorescence and corresponding to the Nephite occupation with intermediate Lamanite intrusion and Mulekite dissatisfactions. During this time period, we witness the most detailed and concentrated history recorded in the Book of Mormon. The books of Mosiah, Alma, Helaman, and 3 Nephi all fall within Period 4 of Santa Rosa.

8. Period 5 of Santa Rosa, dating from AD 200 to AD 500, manifests reduced population of the site. The year AD 350 is crucial in Book of Mormon history because that was the year the Nephites made a treaty with the Lamanites in which the Lamanites were given all of the land southward (see Mormon 2:28–29). Zarahemla was in the land southward, and Santa Rosa is southward of the Gulf Coast and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. During this same time period, Santa Rosa manifested a decline in population and demonstrated rather distinct Lamanite Maya culture patterns.15

9. A significant date was discovered in the 1960s by the New World archaeological Foundation at the Maya site of Chiapa de Corzo, not far from Santa Rosa. The date represents the oldest long count (Baktun, Katun, Tun, Uinal, Kin) date to be discovered at that point in Mesoamerica. That date corresponds to the early part of December 36 BC when the Nephites were driven out of the land of Zarahemla and then moved to the land of Bountiful (see Helaman 4:4–6).

10. The city of Chiapa de Corzo along the Grijalva is a strong candidate for the city/land of Sidom where the ostracized Nephites fled in the first century BC. It is also the place where Zeezrom was healed by Alma and Amulek: “And then Alma cried unto the Lord saying: O Lord our God, have mercy on this man, and heal him according to his faith which is in Christ. . . . And Alma baptized Zeezrom unto the Lord; and he began from that time forth to preach unto the people. And Alma established a Church in the land of Sidom” (Alma 15:10, 12–13). The city of Chiapa de Corzo is located about ten miles east of Tuxtla Gutierrez and is approximately thirty miles northwest of the inundated archaeological site of Santa Rosa.

11. The archaeological site of La Libertad appears to be in the precise location along the Grijalva River (the river Sidon) to be the city of Manti. That is, the headwaters of the Grijalva River come out of the mountains, flow past the archaeological site of La Libertad (Manti), and travel from the east toward the west through the Chiapas valley (land of Zarahemla)—exactly as described in the Book of Mormon. That is, the city of Manti was in the land of Zarahemla bordering the land of Nephi, and the river Sidon had its beginnings in the mountains of the land of Nephi. The land of Manti appears to extend to the top of the mountain where the river Sidon begins. On the other hand, the city of Manti appears to be located at the base of the mountain.

Speaking of La Libertad, Gareth W. Lowe says that it “appears to be 100 percent Preclassic in date,” which is 100 percent Book of Mormon time period. Further, “La Libertad appears to be one of the most important Preclassic sites so far located in the Central Depression.”16 And according to John L. Sorenson, “Manti itself seems likely to have been at the major ruin of La Libertad. It sits at the confluence of three large tributaries that form the Grijalva River just below the big site, and the required wilderness is immediately adjacent to the site.”17 Thus, the dating of La Libertad (Manti) and its location on the Grijalva River (river Sidon) give definitive, significant support to the Grijalva River’s being the river Sidon.

Originating in the mountains of Guatemala from a southeasterly direction, the Grijalva River runs though the entire Chiapas depression, an area about twenty-five miles wide and over a hundred miles long. The river runs in a northeastern direction until it reaches the Sumidero Canyon in the lower Grijalva where it turns north and winds its way to the Gulf of Mexico.

We have several strong reasons for placing the heartland of the land of Zarahemla in the Chiapas valley along the Grijalva River. The reasons we favor the heartland of Zarahemla in the Chiapas depression are as follows:

1. It fits the directional and distance requirements for Mosiah to lead a group of people from Kaminaljuyu, Guatemala, the logical location of the city of Nephi, to the city of Zarahemla.

2. It fits the directional requirements for the people of Zarahemla to come up into the south wilderness.

3. It allows for a Zarahemla east wilderness in the Peten of Guatemala with its archaeological ruins and fortified cities.

4. It allows the Isthmus of Tehuantepec to play its proper role in Book of Mormon geography as the narrow neck of land.

5. As explained in the next section, it permits the Limhi expedition to bypass Zarahemla and wander through the state of Tabasco—in the area proposed as the “land among many waters”—to get into the land northward.

6. It is in an adequate location for Alma and Limhi to return to Zarahemla through an ancient trail that passed over the narrow mountain range known as the “narrow strip of wilderness” in the Book of Mormon.

7. It is in the proper general area for language development—that is, from 600 BC–AD 200, we witness a written language in use that was adopted by the later Classic Maya culture.

8. Ample archaeological population centers are found in the Chiapas valley during the 180 BC–AD 350 time period when much of the Nephite history in the land of Zarahemla occurred.

9. The archaeological ruins of Santa Rosa located in the upper Grijalva valley present compelling evidence as the city of Zarahemla.

10. The archaeological ruins of La Libertad are at precisely the correct elevation and location along the Grijalva to be the city of Manti in the land of Zarahemla.

11. A decline in population occurred in the area around AD 350, coinciding with the time period when the Nephites were forced to leave the land southward.

The findings of the New World Archaeological Foundation in the Chiapas central depression clearly suggest to Book of Mormon readers that the Grijalva River is the river Sidon of the Book of Mormon.

The Limhi Expedition

About 121 BC, king Limhi, living in the land of Nephi among the Lamanites, commissioned an expedition of forty-three men to travel to the land of Zarahemla so they “might appeal unto our brethren to deliver us out of bondage” to the Lamanites:

And they were lost in the wilderness for the space of many days, yet they were diligent, and found not the land of Zarahemla but returned to this land, having traveled in a land among many waters, having discovered a land which was covered with bones of men, and of beasts, and was also covered with ruins of buildings of every kind, having discovered a land which had been peopled with a people who were as numerous as the hosts of Israel. (Mosiah 8:8; emphasis added)

Limhi’s grandfather, Zeniff, had previously traveled the route from Nephi to Zarahemla and from Zarahemla to Nephi, and the Zeniff-Noah-Limhi Nephites had lived in the land of Nephi only about sixty years. Oral history probably dictated the general direction and approximate time of travel to the land of Zarahemla. But the trail to get there would have been lost. We can readily envision the instructions that were given as the Limhi expedition made plans to depart: “The best way to get to Zarahemla is to go to the head of the river Sidon in the wilderness and then follow the river down out of the wilderness until you reach the land of Zarahemla. Continue to follow the river, and before long you’ll arrive at the city of Zarahemla.”

From our perspective, the Limhi expedition did as instructed. However, they probably found the headwaters of the Usumacinta River, which are relatively close to the headwaters of the Grijalva River, and followed the Usumacinta rather than the Grijalva. That is, both rivers originate near each other in the mountains of Cuchumatanes, and both empty into the Gulf of Mexico in close proximity to each other.

The primary evidence that they followed the Usumacinta rather than the Grijalva is associated with the “land among many waters” through which they traveled. Any candidate for a “land among many waters” must be located in such a manner that the people involved in the Limhi expedition would pass by both Zarahemla and the narrow neck of land without realizing they had done so.

Such a place does exist. An area that qualifies itself in distance, location, direction, and size is the area where the massive water pools, lagoons, and river systems drain from the Chiapas mountains into the Gulf of Mexico in the states of Tabasco and Campeche.

The average rainfall in the area between Villahermosa, Tabasco, and Ciudad Carmen, Campeche, is among the highest in the world and is comparable to the rainfall on the island of Laie, Hawaii. This Mesoamerican sea-level area, characterized by the many river systems and the high rainfall, has lagoons of stagnant water—producing massive swamplands and making travel through the area very difficult. It wasn’t until the middle of the twentieth century that bridges were built across the rivers, thus allowing motorized vehicles to travel from Tabasco to the Yucatan.

In all probability, in searching for Zarahemla, the Limhi expedition dropped down from the highlands of Guatemala and located the wrong river stream in the wilderness of Cuchumatanes. Because they probably followed the Usumacinta River route, the Limhi expedition ended up right in the middle of the great lagoon systems described above. Their diligence would then take them to the west without their realizing they had passed through the Isthmus of Tehuantepec—the narrow neck of land. That location places them in the territory of the Jaredites, where they discovered the ancient ruins of the Jaredites, which they initially thought were the ruins of Zarahemla (see Mosiah 21:26).

Figure 5. Proposed route of the Limhi expedition along the Usumacinta River, through the land among many waters, across the top of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and thence into Jaredite territory. This route was a natural outcome if their instructions were to “find the headwaters of the Sidon and then follow the Sidon to Zarahemla.” We propose that they found the headwaters of the Usumacinta, which are relatively close to the headwaters of the Grijalva. Based on archaeological evidence, had they found and followed the Grijalva, as some Book of Mormon scholars propose, they would have encountered thousands of Nephites who spoke their language and who would have told them where they were. Coincidentally, had they followed the Grijalva, they would not have found the twenty-four gold plates containing a record of the Jaredite high civilization.

Proof that they followed the Usumacinta rather than the Grijalva is found from archaeological evidence associated with both the Usumacinta and the Grijalva. Had they followed the Grijalva, they would have discovered thousands of Nephites who spoke their language and dozens of Nephite cities. However, they could not have found Nephites and Nephite cities along the Usumacinta because no Nephites lived there in 121 BC.

The outcomes of the Limhi expedition give tangible evidence that the Grijalva River—not the Usumacinta River—is the river Sidon of the Book of Mormon.

The Day and a Half’s Journey

A careful analysis of Alma’s missionary journeys in the land of Zarahemla reveals relevant information about the river Sidon. Some geographic outcomes of Alma’s journeys are the following:

• The city and valley of Gideon were on the east of the river Sidon: “And now it came to pass that when Alma had made these regulations he departed from them, yea, from the church which was in the city of Zarahemla, and went over upon the east of the river Sidon, into the valley of Gideon, there having been a city built, which was called the city of Gideon, which was in the valley that was called Gideon” (Alma 6:7).

• The land of Melek was on the west of the river Sidon by the borders of the wilderness: “And it came to pass in the commencement of the tenth year of the reign of the judges over the people of Nephi, that Alma departed from thence [city of Zarahemla] and took his journey over into the land of Melek, on the west of the river Sidon, on the west by the borders of the wilderness” (Alma 8:3).

• The city of Ammonihah was three days of travel to the north of the land of Melek: “So that when he had finished his work at Melek he departed thence, and traveled three days’ journey on the north of the land of Melek; and he came to a city which was called Ammonihah” (Alma 8:6).

• Alma left Ammonihah and headed toward Aaron before turning around and returning to Ammonihah: “Now when the people had said this, and withstood all his words, and reviled him, and spit upon him, and caused that he should be cast out of their city, he departed thence and took his journey towards the city which was called Aaron. . . . And it came to pass that while he was journeying thither, . . . an angel of the Lord appeared unto him, saying: . . . I am sent to command thee that thou return to the city of Ammonihah” (Alma 8:13–15).

• Alma left Ammonihah and “came out even into the land of Sidom”: “And it came to pass that Alma and Amulek were commanded to depart out of that city; and they departed, and came out even into the land of Sidom” (Alma 15:1).

• Alma left Sidom and returned to the city of Zarahemla: “Alma . . . took Amulek and came over to the land of Zarahemla, and took him to his own house” (Alma 15:18).

These accounts of Alma’s missionary journeys show that many cities were located along the river Sidon. As noted earlier, that is a routine outcome from the work of the New World Archaeological Foundation in connection with the Grijalva River.

Of particular interest are the geographic pointers associated with Melek and Ammonihah. That is, Melek was west of Sidon “by the borders of the wilderness,” and Ammonihah was three days of travel time to the north of Melek.

A few months after Alma’s visit to Ammonihah, we are told the following:

There was a cry of war heard throughout the land.

For behold, the armies of the Lamanites had come in upon the wilderness side, into the borders of the land, even into the city of Ammonihah, and began to slay the people and destroy the city.

And now it came to pass, before the Nephites could raise a sufficient army to drive them out of the land, they had destroyed the people who were in the city of Ammonihah. . . .

And thus ended the eleventh year of the judges, the Lamanites having been driven out of the land, and the people of Ammonihah were destroyed; yea, every living soul of the Ammonihahites was destroyed, and also their great city, which they said God could not destroy, because of its greatness. (Alma 16:1–3, 9; emphasis added)

In this instance, the Lamanites invaded the territory of the Nephites by entering “in upon the wilderness side.” Thus, we propose that the Lamanites traveled along the Pacific coast and then moved through the wilderness to Ammonihah where they proceeded with their complete annihilation of the people of Ammonihah.

The upshot of this military strategy was very upsetting to the Nephites. As a result, they established a defensive barrier so the Lamanites could neither move into Nephite territory via the wilderness near Melek and Ammonihah nor move into the land northward via the narrow pass. The account of this defensive line is told from the perspective of the Lamanite king in the land of Nephi while the sons of Mosiah were there proselyting:

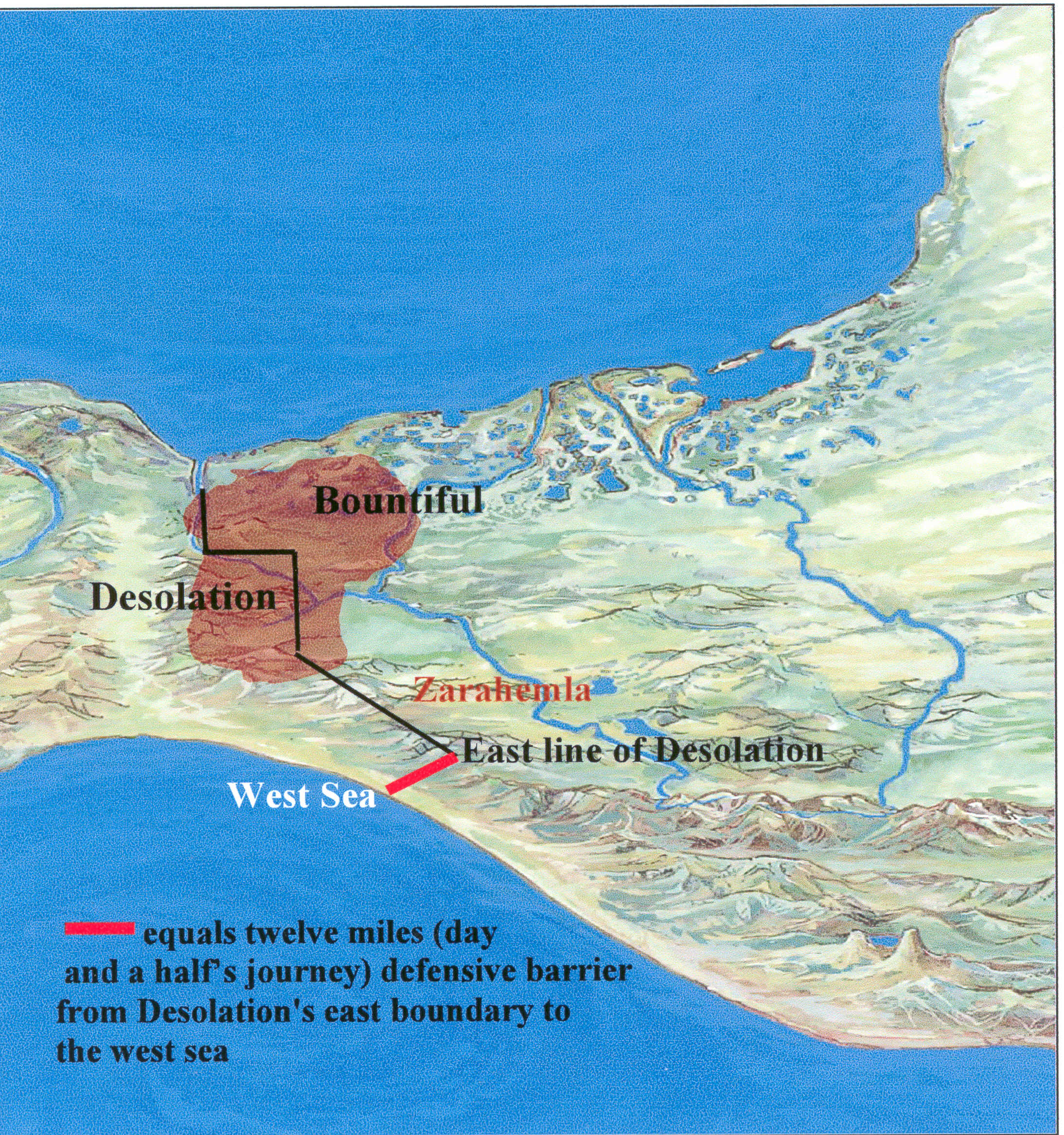

And now, it was only the distance of a day and a half’s journey for a Nephite, on the line Bountiful and the land Desolation, from the east to the west sea; and thus the land of Nephi and the land of Zarahemla were nearly surrounded by water, there being a small neck of land between the land northward and the land southward.

And it came to pass that the Nephites had inhabited the land Bountiful, even from the east unto the west sea, and thus the Nephites in their wisdom, with their guards and their armies, had hemmed in the Lamanites on the south, that thereby they should have no more possession on the north, that they might not overrun the land northward.

Therefore the Lamanites could have no more possessions only in the land of Nephi, and the wilderness round about. Now this was wisdom in the Nephites—as the Lamanites were an enemy to them, they would not suffer their afflictions on every hand, and also that they might have a country whither they might flee, according to their desires. (Alma 22:32–34; emphasis added)

Verse 32 is one of the most controversial geographical statements in the Book of Mormon because it is so often misread by readers. We read it with the following interpretation: “It was only the distance of a day and a half’s journey for a Nephite from the boundary line of Bountiful and Desolation to the west sea.”

Since the initial publication of the Book of Mormon in 1830, many of its readers have routinely wanted a Nephite to cross the narrow neck of land from ocean to ocean in a day and a half. This verse does not say that. It does not say from the east [sea] to the west sea. It says “from the east to the west sea.” It simply states that the east orientation is the dividing line between Bountiful and Desolation. The west orientation is the west sea, which we believe is the Pacific Ocean by the Gulf of Tehuantepec—from the Alma 22 perspective of the Lamanite king and the sons of Mosiah in the land of Nephi. According to our on-site investigations of this geographic area, the day-and-a-half marker begins near the archaeological site of Tonala (candidate for the city of Melek) on the east and ends at the ocean fishing village of Paredon on the west. The distance is twelve miles, which is consistent with Maya travel distance of eight miles a day—or twelve miles in a day and a half. “For a Nephite,” from our perspective, is simply Mormon’s way of saying that in the Nephite measuring system, a day-and-a-half’s travel time is equal to about twelve miles.

Also of interest is the name of the village located on the ocean’s front (west sea). It is Paredon. Pared is a Spanish word that means “wall,” and Paredon means a “big wall.” The local people tell of an ancient wall that was built beginning at the ocean, by the cemetery, and that extended directly east toward the mountain twelve miles away. This historical fact is very important because to this very day, an immigration checkpoint is located in the same area near Tonala. This is a crucial landmark because the high, rugged mountains on the east and the Gulf of Tehuantepec on the west provide a natural defensive area to inhibit or prohibit people from entering through the wilderness into the central depression of Chiapas or to travel through the Isthmus of Tehuantepec into areas of Mexico that are west (and “northward”) of the isthmus.

Whether guards were posted at critical points or whether a wall was built along the entire defensive line, the results would be the same. The motive was to keep the Lamanites from traveling into the land of Zarahemla or into the land northward. That motive was prompted by the Lamanites’ unimpeded invasion through the wilderness and into the city of Ammonihah: “The [Lamanites] took their armies and went over into the borders of the land of Zarahemla, and fell upon the people who were in the land of Ammonihah and destroyed them” (Alma 25:2).

When we pursue the Chiapas depression as the land of Zarahemla, Melek is located along the mountain range west of the archaeological site of Santa Rosa. Melek may have been in the Rio Pando Valley where the ruins of Tonala are located. Ammonihah was located three days’ travel time (about twenty-four miles) north of Melek (Tonala), which would place it, according to our calculations, north of the city of Arriaga near the archaeological mound of El Mirador (not to be confused with El Mirador in northern Peten; see Alma 8:3–6).

The above information is extremely important because it not only provides us with location, distance, direction, and a name correlation but also provides us with the motive for this being the area of the fortification line, which is a distance of a day and a half’s journey for a Nephite defender. The purpose of the fortification wall or line was to keep the Lamanites from coming along the coast from Guatemala toward Mexico—or from the land of Nephi to the land of Zarahemla: “Thus the Nephites in their wisdom, with their guards and their armies, had hemmed in the Lamanites on the south, that thereby they should have no more possession on the north, that they might not overrun the land northward” (Alma 22:33; emphasis added).

As mentioned earlier, prior to the time the Nephites built or manned the day-and-a-half fortification barrier, the city of Ammonihah was vulnerable to an attack from the Lamanites. And also, as noted earlier, Alma started his missionary endeavors in the city of Zarahemla and then went on the east side of the river Sidon and up to the valley of Gideon. He returned to Zarahemla for a time and then went to the west mountains to Melek. From there, he traveled north three days to the land of Ammonihah (see Alma 8:6–9). All geographic areas mentioned are in close proximity to each other.

In summary, as stated in Alma 22:33, the Nephites were wise to keep the Lamanites from going in the back door of Zarahemla and to keep them from going into the land northward via the narrow pass through the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, not far from Paredon, “the big wall."

Where are the geographic territories of Melek (Tonala), the entrance to the narrow neck of land (Isthmus of Tehuantepec), and the defensive barrier of a day and a half’s travel from the east to the west sea (Tonala to Paredon on the Pacific Ocean) in relation to the Grijalva River and the Usumacinta River? The answer obviously is that these geographic territories are associated with the Grijalva River—another tangible evidence that the Grijalva, not the Usumacinta, is the river Sidon of the Book of Mormon.

Figure 6. The defensive line (Alma 22:32) that is the length of a day and a half’s journey (about twelve miles) in the Nephite measuring system runs from Desolation’s east boundary to the Pacific Ocean—or the west sea. The purpose of the twelve-mile defensive line was to keep the Lamanites from getting into Zarahemla and from going into the land northward (see Alma 22:33). Today, the twelve-mile line runs from the archaeological ruins of Tonala to the town of Paredon, which is located on the seacoast. Paredon means “big wall,” and remnants of the wall can still be detected. The twelve-mile line runs from the mountains to the ocean.

A careful examination of the Book of Mormon results in several criteria that must be met by any geographic area being considered as the New World setting for the Book of Mormon. When those criteria are applied to all possible New World settings, Mesoamerica—and only Mesoamerica—meets all the criteria.

Those criteria also support the Isthmus of Tehuantepec—and only the Isthmus of Tehuantepec—as the narrow neck of land of the Book of Mormon.

Our contention is that all major geographic locations of the Book of Mormon (exclusive of cities) should be identifiable with a combination of information from the Book of Mormon itself plus information from the archaeological and historical records of Mesoamerica. This article examines only one of those geographic locations, the river Sidon, from the perspective of the two major rivers of Mesoamerica—the Grijalva River and the Usumacinta River. Based on our analyses, we conclude that the Grijalva River is the river Sidon of the Book of Mormon for the following reasons:

1. The Chiapas central depression meets all requirements to be the land of Zarahemla, and the archaeological site of Santa Rosa along the Grijalva River in the central depression meets all requirements to be the city of Zarahemla. The directions and distances from these two areas in conjunction with the Isthmus of Tehuantepec meet the requirements for the Jaredites’ hunting preserve in the land southward and the Nephites’ wilderness of Hermounts. The modern name of the area comprising the Jaredites’ hunting preserve and the Nephites’ wilderness of Hermounts is the wilderness area of Uxpanapa-Chimalapa. Its location near the proximity of the Grijalva River supports the Grijalva—not the Usumacinta—as the river Sidon.

2. Book of Mormon events in the land of Zarahemla require archaeological evidence of numerous sites in existence during the Preclassic Period of about 300 BC to AD 250. No adequate archaeological sites dating to the Preclassic have been discovered along the Usumacinta River. That is, even though major archaeological sites such as Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan are located on the Usumacinta, such sites are all Postclassic Period sites. On this basis, the Usumacinta cannot be the river Sidon.

3. The New World Archaeological Foundation did extensive archaeological investigations along the Grijalva River in the Chiapas central depression and documented the existence of several dozen Preclassic sites that qualify as Book of Mormon cities in the land of Zarahemla, including very logical sites for the city of Zarahemla and the city of Manti. On this basis, the Grijalva River satisfies all Book of Mormon conditions for the river Sidon.

4. The 121 BC Limhi expedition set out from the land of Nephi to find the land of Zarahemla, but the expedition members were unsuccessful in their efforts. They probably went from the land of Nephi to what they thought were the headwaters of the river Sidon and then followed the resultant river in anticipation of arriving in the land of Zarahemla. However, because the headwaters of both the Usumacinta River and the Grijalva River originate in near proximity to each other in the Cuchumatanes mountain range, they probably followed the Usumacinta into the Book of Mormon land among many waters and thence to the land of Desolation where they discovered the ruins of the Jaredite civilization and thought they had discovered the land of Zarahemla. If they had followed the Grijalva River on their expedition, they would have discovered dozens of Nephite cities and thousands of Nephites who would have verified they were in the land of Zarahemla along the river Sidon. The Limhi expedition gives substantial evidence that the Grijalva River—not the Usumacinta River—is the Book of Mormon’s river Sidon.

5. The motive for the Alma 22:32 defensive line of a day and a half’s journey of about twelve miles requires the defensive line to run from the east to the Pacific Ocean on the west either at Tonala/Paredon or nearby. That location in conjunction with the nearby territory requires a close relationship with the river Sidon, which then clearly favors the Grijalva River as the Sidon.

At this point, some readers may think that the issue of the Grijalva versus the Usumacinta as the river Sidon is not a major one because the distances between the Grijalva and Usumacinta rivers are not that great. However, before anyone arrives at that conclusion, we suggest that he or she fly over the wilderness area from Comitan, Chiapas, to Yaxchilan, Chiapas. That area consists of massive canyons, almost impenetrable forested wilderness, and at least seven major river tributaries that drain into the Usumacinta basin. In other words, no direct relationship exists between the Usumacinta River and the west sea (Pacific Ocean), a Book of Mormon requirement.

We could explore additional evidences that support the Grijalva River as the river Sidon—such as the overall geography of the land southward, the pottery trail from Kaminaljuyu (proposed city of Nephi) to Santa Rosa, additional name correlations beyond “Hermounts” and “Tehuantepec,” distances associated with other Sidon-related geographic features, and additional information about the geographic lay of the land, such as the narrow strip of wilderness. However, we feel that the evidences we have presented are adequate to prove conclusively our perspective that the Grijalva River is the river Sidon.

Therefore, based on our analyses, we repeat unequivocally that the Grijalva River, which flows through the central depression of the state of Chiapas, Mexico, is the river Sidon of the Book of Mormon. We invite all Book of Mormon readers to evaluate our evidence and either accept it at face value or prepare a valid rebuttal. We especially encourage all readers to discontinue any attempts to label the Usumacinta River as the river Sidon.

The Book of Mormon is a real account about real people who lived in Mesoamerica. The Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the Uxpanapa-Chimalapa wilderness area, the central depression of Chiapas, the Grijalva River, the land among many waters at the mouths of the Grijalva and Usumacinta rivers, and the Pacific Ocean “just happen” to be in the correct locations so they can satisfy all conditions of the Book of Mormon associated with the river Sidon. The above analysis supports our often-repeated admonition that the more we know about the geography of the Book of Mormon, the more we know about the Book of Mormon.

1. Lawrence L. Poulsen, “The Land of Zarahemla,” www.poulsenll.org/bom/Zarahemla.html (accessed September 24, 2008).

2. For a comprehensive discussion of these five statements, see Joseph Lovell Allen and Blake Joseph Allen, Exploring the Lands of the Book of Mormon, 2nd ed. (Orem, UT: Book of Mormon Tours and Research Institute), 2008.

3. “Uxpanapa-Chimalapa Region,” www.botany.si.edu/projects/cpd/ma/ma2.htm (accessed September 27, 2008); emphasis added.

4. Melesio Ortega Martinez, Resena Historico de Tehuantepec (Oaxaca, Mexico: H. Ayuntamiento Constitucional de Tehuantepec, 1998), 5; see also Lawrence L. Poulsen, “The Light Is Better Over Here,” The Farms Review 19, no. 2 (2007): 16–17; Antonio Penafiel, Nombres Geograficos de Mexico (Mexico, DF: Litoimpresores, 1977), 54; and Allen and Allen, Exploring the Lands of the Book of Mormon, 12–13, 46, 583.

5. Poulsen, “The Light Is Better Over Here,” 17.

6. See Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube, Chronicle of the Maya kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), 138–54.

7. See Martin and Grube, Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens, 116–37.

8. See Charles Golden and Andrew Scherer, “Border Problems: Recent Archaeological Research along the Usumacinta River,” The PARI Journal 7, no. 2 (Fall 2006): 7–13.

9. Thomas Stuart Ferguson, Introduction Concerning the New World Archaeological Foundation, Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, no. 1 (Orinda, CA: NWAF, 1956), 3. For additional information about the founding of the NWAF and its resulting achievements, see Daniel C. Peterson, “On the New World Archaeological Foundation,” The Farms Review 16, no. 1 (2004), 221–33.

10. See Agustin Delgado, Excavations at Santa Rosa Chiapas, Mexico, Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, no. 17 (Provo, UT: New World Archaeological Foundation, Brigham Young University, 1965), 2.

11. Gareth W. Lowe, The Chiapas Project, 1995–1958: Report of the Field Director, Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, no. 1 (Orinda, CA: New World Archaeological Foundation, 1959), 1.

12. John L. Sorenson, An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1996), 155.

13. Gareth W. Lowe, Archeological Exploration of the Upper Grijalva River, Chiapas, Mexico, Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, no. 2 (Orinda, CA: New World Archaeological Foundation, 1959), 78.

14. Sorenson, An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon, 155–56; see also Donald L. Brockington, The Ceramic History of Santa Rosa, Chiapas, Mexico, Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, no. 23 (Provo, UT: New World Archaeological Foundation, Brigham Young University, 1967), 60–61.

15. For a further discussion of Santa Rosa Periods 3, 4, and 5, see Delgado, Excavations at Santa Rosa, Chiapas Mexico, 79–81. Our use of the term “Lamanite Maya” here is intentional. From our perspective, based on a merger of the historical data in the Book of Mormon and the archaeological and historical data from Mesoamerica, both the Nephites and the Lamanites were Maya. That is, they were the same people; and we frequently distinguish them in our research via the terms “Nephite Maya” and “Lamanite Maya.”