Names and Maya Glyphs

by Daniel Johnson

Many unique names appear in the Book of Mormon throughout the long histories of several cultures,

however, we are only given a tiny selection from what must have been thousands of personal names. Some

appear only within its pages and others have precedents from the Bible and other ancient documents. What

was a common Nephite or Jaredite name? Did they adopt new local names from surrounding cultures in the

New World? And most importantly, can any trace of these names be found in surviving records from ancient

American peoples?

According to some LDS authors, the answer to the last question is yes. In Exploring the Lands of the Book of

Mormon, Joseph Allen cites the work of LDS archaeologist Bruce Warren to show that the name and birth

date of a Jaredite king named Kish are found in Maya glyphs on the Temple of the Cross in Palenque.1 This

seemed like a rather bold statement and since there have been concerns about the accuracy of Allen’s

assertions in the past, we decided to look into the matter. After all, why would an ancient Jaredite king be

mentioned in a Classic Maya text dealing with royal lineage in Palenque? We are pleased to report that Allen

is basically correct, but his description is rather brief and what he leaves out is quite interesting and adds

considerably to our understanding.

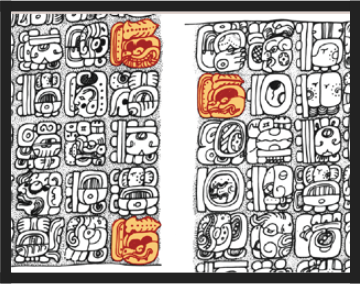

The Temple of the Cross was built by Kan Balam, son of the great king Pakal. The famous central image of Kan

Balam receiving divine authority from his deceased father, centered around the Maya cross or sacred tree of

life, is flanked on either side by hieroglyphic texts. These writings proclaim his divine right to rule through his

lineage. The right side traces his immediate ancestry through his father and up to the founder of Palenque’s

dynasty, a king named Kuk Balam I who acceded to the throne in ad 431. The left side goes back even further,

recording the births of deities from the previous cycle of creation.2 The name Allen refers to appears twice

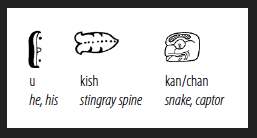

on the left panel and once on the right. It is made up of three different glyphs that are read U-Kix-Kan. In transliterated Mayan phonetics, the sound “SH” is written as “X.” The crucial part of the name, Kish, is actually a Mayan word meaning “stingray spine.” The three phonetic components are really words in this case, but they fit together to form a compound

name, much as letters fit together to form words. Kish’s birth date is given in the Maya Long Count and would be rendered as 11 March 993 bc. According to the text, he was crowned as a divine king of Palenque at the age of 26. Even though his name first appears on the legendary or divine textual panel, he is understood to be human and not a god because of his

realistic age at the time he became king.3

Archaeologists are unsure if he was a real person or not. Although Palenque was inhabited during Preclassic times, nothing has survived from the time of Kix. If he was real, there was a gap of almost 1,400 years between his coronation and that of the acknowledged founder of Palenque’s dynasty. In fact, when Kix became a king, Palenque as we would recognize it did not even exist. There may have been a settlement there, but what it was called or who lived there is unknown. But if this is the same Jaredite king, should not his name in the Book of Mormon be something like Ukishkan? Not necessarily. Many Maya kings had lengthy royal titles that shared many common elements with eachother. Most kingly names included a long sequence of glyphs that represented the names of gods or important animals.4

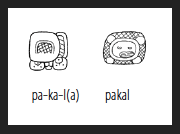

Kinich Hanaab Pakal is the actual name of Pakal, the well known king of Palenque. Another Palenque king is named U-Pakal-Kinich-Hanaab-Pakal.5 In the case of U-Kix-Kan, U can be a third person pronoun or simply a phonetic sound and Kan means “serpent” and can refer to a kingdom often associated with the site of Calakmul. These are common elements found in the names of many Maya kings. The distinguishing part of his name appears to be the stingray spine, or Kix. But why would Kan Balam referto this possibly semi-mythical person, even describing him as a king of Palenque? By writing down Kix’s birthdate, he is making a direct connection to a king we now identify as Olmec. The Maya inherited or borrowed many aspects of their society from this mother culture of Mexico. For Kan Balam, linking his lineage to theOlmecs legitimized his claim to the throne. Since many LDS scholars identify the Jaredites as connected to the Olmecs, this may be the Kish from the Book of Mormon.

However, the reading of kix for the stingray spine glyph has come into question in recent years. The glyph

does represent a stingray spine, but since these items were used for sacrificial bloodletting, it may also signify

a needle, fang, or other sharp implement used for the same purpose. In a wider sense, it also represents

creation and conception, so the same glyph can refer to parentage. Cross-referencing these words in Mayan

dictionaries suggests that the reading of this glyph should be kokan.6 If this is correct, the name of the king

in questions would be U-Kokan-Kan. But a Yucatec Mayan word, kóoh-kan, means “fang of the serpent” and

there is the suggestion that the stingray spine glyph may have originated as a snake’s tooth. If this is the case,

the name of the mythical Palenque ruler in question would mean, “He is the snake tooth of snake,” which

does not make much sense. Apparently for this reason alone, that definition is rejected in favor of “stingray

spine” for kokan.7

It appears now that the case for finding the Jaredite king Kish is not so iron clad. The Classic-era Maya who wrote about this ancient Olmec king wrote his name as “He is the Bloodletter of the Snake” or “His Snake Spine,” but would they have called him U-Kokan-Kan instead of U-Kix-Kan? We may never know for sure. Even in recent scholarly literature, he is sometimes referred to as U-Kix-Kan. The name Kix-Chan (or variant spellings of it) is still found among the Maya in areas of the Petén in Guatemala.8 The stingray spine or bloodletter glyph, whether read as kokan, kix, or some other word, can represent fathership when used as part of a name. According to some Mayan dictionaries, the serpent glyph can also mean guardian or captor.

(All glyphs adapted from John Montgomery, Dictionary of Maya Hieroglyphs.)

Of the many personal names contained in the Book of Mormon, some are Biblical or directly linked to the Levant. Even Kish is found in the Old Testament as the name of several individuals, including the father of Saul, first king of Israel. Also, a quick glance at a dictionary of Maya glyphs shows that they lack several letters found in Hebrew. Mayan has no counterpart for D, F, G, R, or V. We excluded Book of Mormon names with these sounds and ones that were obviously brought from the Middle East. Our experiment was to find names that might be indigenous to Mesoamerica or could easily be rendered with Maya glyphs.

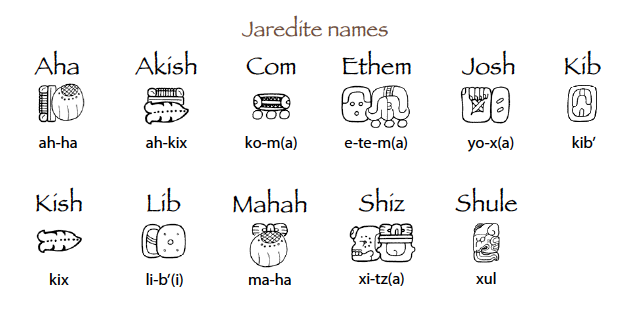

The following diagram shows a sample of Jaredite names rendered in Classic Maya glyphs. The orthography has been simplified somewhat for readability. Because of the redundancy in some of the glyphs, these names could have been written using other combinations, but this should suffice. A few of these actually may have meanings in Mayan. Ah-ha means “he of the water” and is similar in meaning to the title ah-naab, which refers to artists. Similarly, ah-kish means “he of the stingray spine.” Kib is the sixteenth day of one of the Maya calendars. Ma-ha can mean “no water,” and xul is the sixth month of a Maya calendar.

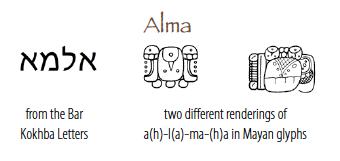

Many Nephite names have their origins in the Old World; some are exactly the same as Biblical names. Even names like Abinadi and Mosiah that are not found in the Bible appear to have Hebrew etymologies. LDS scholars and linguists have published insightful and thought-provoking studies showing that some names found exclusively in the Book of Mormon have unexpected Hebrew and Egyptian origins.10 Of particular interest is the name Alma. For many years, it was not recognized as a masculine name outside of the Book of Mormon and has been criticized as being a feminine form in both Hebrew and Latin. Even though it is easily rendered with Maya glyphs, it has not been included in our list of Nephite names because recent discoveries show that it is actually an ancient Hebrew name. It appears in the Bar Kokhba letters, dated to ad

130, referring to someone named Alma ben-Yehuda (Alma, son of Judah).11 This find, certainly unknown to Joseph Smith, seems to validate the masculine name Alma as authentic, but critics may point out that since these writings did not exist until centuries after Lehi’s departure, they cannot be the source of the name.

be much calendars. Ma-ha can mean “no water,” and xul is the sixth month of a Maya calendar. Many Nephite names have their origins in the Old World; some are exactly the same as Biblical names. Even names like Abinadi and Mosiah that are not found in the Bible appear to have Hebrew etymologies. LDS scholars and linguists have published insightful and thought-provoking studies showing that some names found exclusively in the Book of Mormon have unexpected Hebrew and Egyptian origins.10 Of particular interest is the name Alma. For many years, it was not recognized as a masculine name outside of the Book of Mormon and has been criticized as being a feminine form in both Hebrew and Latin. Even though it is

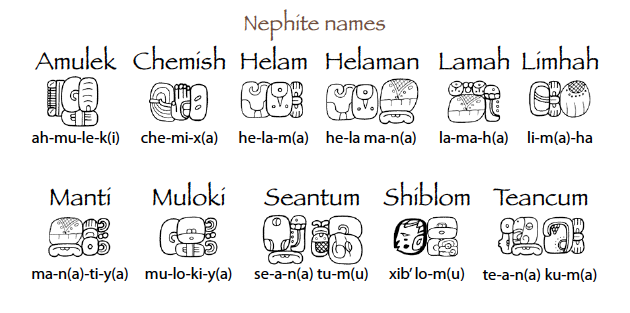

easily rendered with Maya glyphs, it has not been included in our list of Nephite names because recent discoveries show that it is actually an ancient Hebrew name. It appears in the Bar Kokhba letters, dated to ad 130, referring to someone named Alma ben-Yehuda (Alma, son of Judah).11 This find, certainly unknown to Joseph Smith, seems to validate the masculine name Alma as authentic, but critics may point out that since these writings did not exist until centuries after Lehi’s departure, they cannot be the source of the name. Notwithstanding that Joseph still somehow came up with an actual ancient Hebrew male name that was unknown at the time, this is true, but the same name has also been found on clay tablets from an ancient Syrian site called Tell Mardikh. They contain writings in a Semitic language similar to Akkadian, rendered in cuneiform that predates the Hebrew alphabet. The name al6-ma is found eight times in the texts.12 These writings by far predate the time of Lehi, so the name Alma maybe much older than previously suspected. We found over 30 Nephite names unique to the Book of Mormon that were compatible phonetically with Mayan. The table below shows some of the names that seemed to work well. A few of these names could

also have Hebrew or Semitic origins, but it is interesting to see how they might look rendered as Maya glyphs. According to Mayan dictionaries, ah-mulek means “he of Mulek” and xib-lom could mean “man of the staff.” While not a perfect match to Teancum, a king named Tecum is mentioned by the Spanish historian Juarros in his records of the dynasties of the Quiché empire in the Guatemalan Highlands.13

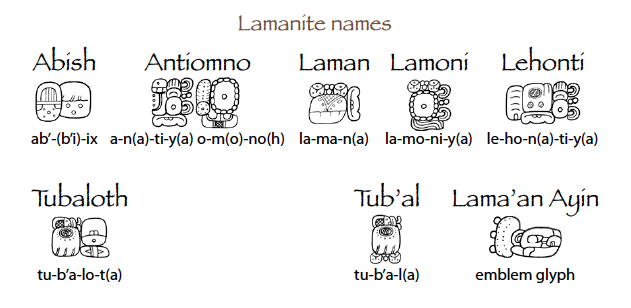

For Lamanite names, there is a much smaller number to examine. Of all the Lamanites depicted in the scriptural record, both wicked and righteous, only a few are named. For some reason, Nephite record keepers did not think it necessary to give us many of their names. There is consequently a much smaller sample upon which to draw, but some surprising results can be seen. The first is the predominance of male names beginning with the letter L. The second is that discarding names that are carryovers or cognates from

Hebrew, like Aaron and Samuel, practically all unique Lamanite names are composed only of phonemes found in Mayan languages. The one exception is Zerahemna, a name that seems obviously derived from Zarahemla. Ab-ix may mean “year of the jaguar” in Mayan. Tubaloth seems to be a word taken directly from Hebrew. Tubal is a name found several times in the Old Testament; the first is Tubal-cain in Genesis 4:22. The second is in Genesis 10:2 as Tubal, grandson of Noah through Japheth. This name was eventually applied to an entire nation or group of people. -oth can be a feminine plural ending in Hebrew. Even though it has a Hebrew etymology, Tubaloth was included because a Classic Maya site in the Guatemalan lowlands is named Tub’al,14 so this appears to be a name that could have been passed down in one form or another among the Lamanites for millennia.

Laman has been included in this list, because even though this name obviously has its roots in the Middle East, it was still in use in the Americas 1000 years later to describe a numerous group of people, so it may have had more of an impact on the surrounding cultures. It is also a Mayan word meaning “submerged.” A site in Belize is known as Lamanai, but that is actually a corruption of its true name, Lama’an Ayin, which means “submerged crocodile.”15 It is truly ancient, with habitation going back as far as 2000 bc. Lama’an Ayin is one of the few examples of a site that has retained its pre-Columbian name. That name has survived since at least the Classic time period, but it is not known how much older it may be.

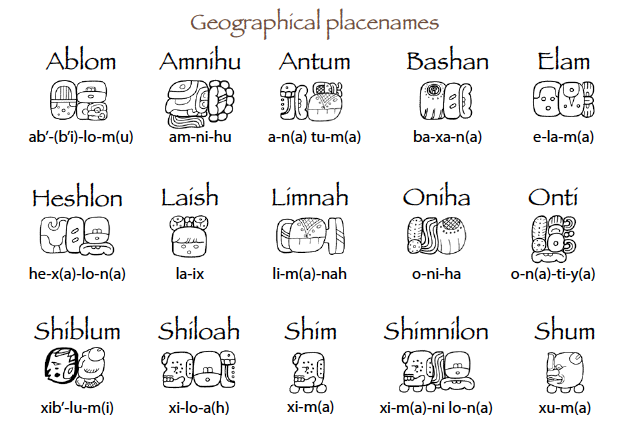

The last category to look at is geographical placenames, usually of lands or cities. In some cases, we know the origin of these names, but many are listed in the Book of Mormon without any provenance, so it is not known if they are of Nephite, Lamanite, Jaredite, or some other origin. As LDS scholars have shown, some like Zarahemla, Jershon, and Cumorah have very close ties to Hebrew.18 But some may have Mesoamerican origins, especially if they can easily be rendered with Maya glyphs. It is likely that some of these names were still in use centuries after the close of the Book of Mormon. Names that were of local origin or did not use sounds foreign to the indigenous languages of the Americas are the best candidates for enduring. The problem is that we do not currently know of any such examples. The names of locations found in modern

Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras are completely different, but they are much more contemporary in nature. Obviously, any Spanish names were given after the Conquest. Many of the names we see on Maya sites were given by later peoples after the cities were abandoned or much later by modern archaeologists. Only in recent decades have some original ancient names come to light. During the height of Maya culture, cities and regions had names like Lakam-Ha, Toktan, Tubal, Naaman, Motul, Yash-Ha, Laman-Ayin, Shukpi, Kan, and Zama. The Book of Mormon placenames shown below would fit right in.

But Classic-era Maya names for regions, polities, and cities only go back as far as the written record of

Maya hieroglyphs. No names exist that can be confirmed to be earlier than the 4th or 5th centuries ad. Both

supporters and critics of the Book of Mormon should realize that for many reasons, it would be virtually

impossible to find names like Nephi or Zarahemla in the archaeological record of Mesoamerica. Names that

would go back that far have probably not survived to this day.

What insights, if any, can be gained from this study? The first suggestion is that a close examination of personal names may shed some light on the language and culture of the people who had them (or at least, their parents). If Book of Mormon peoples had names with vowels, consonants, and phonetic combinations not

found in languages indigenous to the Americas, then we must look elsewhere for their spoken tongue. We

know that Lehi’s group arrived with a knowledge of Hebrew and Egyptian. Mulek’s group arrived with the

same background in Hebrew. We do not know what language the Jaredites spoke. Our comparisons rest on

the assumption that Joseph Smith gave us correct renderings of these ancient names. There is always the

possibility of error here and our English pronunciation of these names differs from other languages. However,

since he spelled out unfamiliar names during the translation process and was under the personal tutelage of

the last Nephite record keeper, it is probably a safe assumption that the transfer of these names into English

was as accurate as possible. Known Biblical names were translated into their English counterparts: Jacob,

Joseph, Isaiah, Benjamin, and so on. Most Hebrew consonants can be satisfactorily rendered in English, so we

are assuming a fairly correct transliteration of names unknown to Joseph Smith or his scribes.

The second suggestion is that the longer these immigrants from the Old World lived in the Americas, the

more they adopted the local indigenous cultures into their own, perhaps evidenced to some degree by the

names they chose for their children. It is likely that righteous Nephites were the slowest to assimilate, perhaps

preferring to remain a “peculiar people” like the Old Testament Israelites. Names that can be easily rendered

in ancient Mesoamerican languages like Mayan may be an indication of this assimilation. Conversely, names

that are difficult or impossible to render satisfactorily in Mesoamerican languages may indicate a lingering

connection to the original Semitic cultures. For example, the names Mormon and Moroni appear at the very

end of Nephite history. Trying to write Moroni in Mayan results in mo-lo-ni-y(a). Mormon is also problematic:

mo-l(o)-mo-n(a). Names like Gid or Gidgiddonah would be impossible without major alterations. Whatever

the lingua franca of the region may have been, Mormon and Moroni must also have spoken a language in

which it would have been easy to pronounce and write their own names. This best candidates are Hebrew

and Reformed Egyptian, both altered by the Nephites. Even if the Nephites eventually adopted a local

language, their prophets and record keepers kept a form of these original languages alive. It is interesting

to note that of the 22 listed Nephite record keepers, 17 had names that had strong Semitic influences or are

difficult, if not impossible, to render satisfactorily in Mayan. It is possible that this particular class of Nephites

(likely direct descendants of Lehi) deliberately chose names from their original cultural heritage for their

children as a reminder of their position before God. This may also be an indication of a lesser amount of

assimilation into the surrounding Mesoamerican cultures.

The preceding examples constitute but a limited treatment of the possibilities for a Mesoamerican origin

of some Book of Mormon names. There remains much more that could be done on this topic. We invite

those that are trained in ancient Mayan languages and hieroglyphs to examine the comparisons we have

made and offer any improvements, comments, or suggestions regarding the meanings and renderings of

the names depicted here. Much has already been done to correlate these names with Old World languages,

but there appears to be a great unexplored area of study in connecting them to the New World. A few

interesting comparisons shown here suggest that some Book of Mormon names could have Mesoamerican

origins. The large number of placenames that can be written in Mayan is especially intriguing. It suggests

that Book of Mormon peoples may have used indigenous names for some of their own locations.

The results presented here are merely tentative and should serve more as suggestions or opportunities

for further study than conclusions. Given the challenging nature of tracing the original pronunciations of

ancient names transmitted through diverse and unrelated languages, much time and effort needs to be

dedicated to this endeavor. It is hoped that this paper will be viewed as an introduction to research on the

topic of Mesoamerican connections to Book of Mormon names.

Notes

(Orem: Book of Mormon Tours and Research Institute, LLC, 2008), pp. 132-133.

2 See Linda Schele and David Freidel, A Forest of Kings (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1990),

The author wishes to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Cal Tolman in the areas of linguistics terminology and ancient languages in the preparation of this paper. pp. 252-254.

3 Ibid.

4 Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube, Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens (London: Thames &

Hudson, 2000), p. 15.

5 Ibid., p. 172.

6 Albert Davletshin, “Glyph for Stingray Spine,” (Moscow: Russian State University for the

Humanities, 2003).

7 Ibid., p. 3.

8 Floyd G. Lounsbury, “The Identities of the Mythological Figures in the Cross Group Inscriptions of

Palenque,” Fourth Palenque Round Table, 1980 (San Francisco: Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, 1985),

p. 57.

9 Stephen D. Houston, Reading the Past - Maya Glyphs (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of

California Press, 1989), pp. 39-40.

10 See John A. Tvedtnes, “Hebrew Names in the Book of Mormon,” 13th Congress of Jewish Studies,

(Jerusalem: 2001)

11 Paul Y. Hoskisson, “What’s in a Name?” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Volume - 7, Issue - 1,

(1998), pp. 72-73.

12 Terrence L. Szink, “New Light: Further Evidence of a Semitic Alma,” Journal of Book of Mormon

Studies: Volume - 8, Issue - 1, (1999), p. 70.

13 See Hubert Howe Bancroft, The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft: The Native Races, vol. V (San

Francisco: L. Bancroft & Company, 1883), pp. 594-595.

14 Nikolai and Grube, Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens, pg. 76.

15 <http://www.famsi.org/reports/98037/section05a.htm>

16

17 Nikolai and Grube, Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens, pp. 22-23.

18 See Tvedtnes, “Hebrew Names in the Book of Mormon.”