Columbus, the “Promised Land,” and the Restoration of the Gospel

Columbus, the “Promised Land,” and the Restoration of the Gospel

Copyright © 2010 by Richard L. Millett

Richard Millett was mission president of the Florida Ft. Lauderdale Mission when it was divided. At that point, he became mission president of the newly created Puerto Rico San Juan Mission with headquarters in San Juan. While serving in the Caribbean, he became acutely interested in Columbus—who made four voyages to the Caribbean and who is still an integral aspect of its history, especially in the Dominican Republic.

Richard learned Spanish as a missionary in Argentina. In addition to his service as mission president in the Caribbean, he has served as director of missionary activities in the Missionary Department, administrative director of business services for the Provo and the International MTCs, president of the Mexico MTC, and mission president of the Chile Santiago East Mission.

Several years ago, he began writing the article that follows as an expression of his appreciation for Columbus and as an outgrowth of his love for the Remnant Seed of the Book of Mormon—most of whom, according to him, claim Spanish as their native language. In that respect, he notes that Columbus indeed discovered “America” as prophesied in the Book of Mormon but also that Columbus never set foot on the soil of the continental United States—facts that say much about the location of the New World “promised land” as it relates to the Book of Mormon.

From the time of the arrival of Lehi and his family in the New World until the destruction of the Nephites as a nation by the Lamanites, history waited for the arrival of Columbus and the beginning of European colonization. These events were a prelude to the restoration of the gospel that followed centuries later in fulfillment of the prayers and prophecies of the prophets and people who lived in the Americas. They foresaw the day when the gospel would be lost from among the Nephites and when the events would transpire that would ultimately lead to their destruction:

Behold, all the remainder of this work does contain all those parts of my gospel which my holy prophets, yea, and also my disciples, desired in their prayers should come forth unto this people.

And I said unto them, that it should be granted unto them according to their faith in their prayers;

Yea, and this was their faith—that my gospel, which I gave unto them that they might preach in their days, might come unto their brethren the Lamanites, and also all that had become Lamanites because of their dissensions.

Now, this is not all—their faith in their prayers was that this gospel should be made known also, if it were possible that other nations should possess the land;

And thus they did leave a blessing upon this land in their prayers, that whosoever should believe in this gospel in this land might have eternal life;

Yea, that it might be free unto all of whatsoever nation, kindred, tongue, or people they may be.

And now, behold, according to their faith in their prayers will I bring this part of my gospel to the knowledge of my people. Behold, I do not bring it to destroy that which they have received, but to build it up. (Doctrine and Covenants 10:46–52)

These words came in fulfillment of the words the Savior spoke to the Nephites at the time He appeared to them in the New World following His resurrection:

And behold, this is the thing which I will give unto you for a sign—for verily I say unto you that when these things which I declare unto you, and which I shall declare unto you hereafter of myself, and by the power of the Holy Ghost which shall be given unto you of the Father, shall be made known unto the Gentiles that they may know concerning this people who are a remnant of the house of Jacob, and concerning this my people who shall be scattered by them;

Verily, verily, I say unto you, when these things shall be made known unto them of the Father, and shall come forth of the Father, from them unto you;

For it is wisdom in the Father that they should be established in this land, and be set up as a free people by the power of the Father, that these things might come forth from them unto a remnant of your seed, that the covenant of the Father may be fulfilled which he hath covenanted with this people, O house of Israel;

Therefore, when these works and the works which shall be wrought among you hereafter shall come forth from the Gentiles, unto your seed which shall dwindle in unbelief because of iniquity;

For thus it behooveth the Father that it should come forth from the Gentiles, that he may show forth his power unto the Gentiles, for this cause that the Gentiles, if they will not harden their hearts, that they may repent and come unto me and be baptized in my name and know of the true points of my doctrine, that they may be numbered among my people, O house of Israel;

And when these things come to pass that thy seed shall begin to know these things—it shall be a sign unto them, that they may know that the work of the Father hath already commenced unto the fulfilling of the covenant which he hath made unto the people who are of the house of Israel. (3 Nephi 21:2–7)

The Restoration could not take place until the climate had been prepared. A free nation among the Gentiles had to be established, and its government had to foster the proper environment for the gospel plan. Columbus had to discover the New World, and freedom had to be established through the shedding of blood in the battle for independence. All these events would be a prelude to the gospel going forth to the nations of the Caribbean.

A Description of Columbus

Although no portraits of Columbus that were painted during his lifetime are available, we do have a description of Columbus: “As to Columbus’s appearance at the time accounts agree: Plainly dressed, he was tall and heavyset, of ruddy complexion, with an aquiline nose set in a long face. His eyes were gray-blue and could sparkle with emotion. Although the widower was only 34, his hair already was white.”1

Who and What Motivated Columbus?

Much has been said about the exploits of Columbus. Many scholars say that his motivation for sailing to the “East Indies” was for self-satisfying reasons. Like the Prophet Joseph Smith, Columbus’s name has been known by “kindreds, and tongues, or that it should be both good and evil spoken of among all people” (see Joseph Smith—History 1:33). How interesting that a prophet of God should be subjected to such scrutiny by the world. In this same light, the world has sought to judge the motivation and deeds of Columbus. Not knowing the source of his inspiration or understanding how the Lord used him to fulfill his eternal purposes could cause scholars to view him with limited vision and insight. Columbus had a part to play in bringing the gospel to the Americas.

Only when we are exposed to the writings and innermost thoughts of Columbus can we appreciate adequately the true understanding of his life and vision. Some scholars maintain that he sought for “God, glory, and gold,” but those who have this vision of this noble man are extremely limited because they do not know how the Lord motivated and used him to fulfill His plan. Regardless of whatever point of view we may have, we cannot deny the influence that Columbus had on the western world.

After Jesus Christ, no individual has made a bigger impact on the Western world than Christopher Columbus. He is commemorated in the names given to streets, cities, rivers and even in the name of a country, yet the reason he dared to embark on his fateful enterprise has never been adequately explained. Although academics have scrutinized every known detail of his career and his voyages, just what impelled him to pursue his dream so doggedly has remained concealed behind a blur of speculation and legend. Why was a humble merchant sailor of little formal learning driven to sacrifice the best years of his life to the launching of so ambitious and farsighted an enterprise?2

The Source of Columbus’s Inspiration

Clearly, regardless of any shortcomings Columbus may have had, he was on a course that was directed by the Lord. The Book of Mormon tells of the role he would play in discovering the western hemisphere and, thus, prepare this part of the world for the eventual restoration of the gospel at a later point in time:

And it came to pass that I looked and beheld many waters; and they divided the Gentiles from the seed of my brethren.

And it came to pass that the angel said unto me: Behold the wrath of God is upon the seed of thy brethren.

And I looked and beheld a man among the Gentiles, who was separated from the seed of my brethren by the many waters; and I beheld the Spirit of God, that it came down and wrought upon the man; and he went forth upon the many waters, even unto the seed of my brethren, who were in the promised land.

And it came to pass that I beheld the Spirit of God, that it wrought upon other Gentiles; and they went forth out of captivity, upon the many waters. (1 Nephi 13:10–13)

We can clearly discern from that reference to Columbus in the Book of Mormon that he did not “discover” America. It had already been discovered by others whom the Lord had previously sent to this “land of promise.” It had been protected from other nations so it could serve as the cornerstone for the message of the Restoration. Columbus did encounter a different people whom he named “Indians,” thinking he had found the Orient. And although we can say that Columbus did not “discover” America, we must, in turn, say that he did bring to light a “new world” that had been hidden from the populaces of Europe and Asia:

Columbus did not in fact discover a new world and thus, initiate American history; rather, he brought two old worlds into permanent contact and thus irrevocably changed the course of world history. . . .

When the Spaniards marched into the basin of Mexico and beheld the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan, they were astounded. Never had they dreamed of encountering an urban center of such size and splendor in the wilds of the “new” continent. Before them stretched a veritable metropolis of some 200,000 inhabitants. A fleet of canoes 80,000 strong accommodated commerce and passenger transport via a well-engineered system of lake-fed canals. This picture differs substantially from the way the precontact Americas have been portrayed traditionally. Indeed, the precontact American cities illustrate (in terms of Western scholarship), the emergence of “high culture” or “true civilization,” and rivaled many of the Old World cities of the 16th century.3

Columbus played an important role in uncovering the peoples and cultures of the Book of Mormon. They had waited for centuries for the Gentiles to find them and to establish a nation whose government would foster and give birth to freedom. With the proper climate established, the way was prepared for the Restoration and for the emergence of the record of the inhabitants of the Americas, the Book of Mormon (see 1 Nephi 13:30–33 and 3 Nephi 21:1–9).

An Early Fascination for the Sea

Most historians believe that Columbus was born in Genoa, Italy, although some believe he spent his childhood in Spain. He had an early fascination that drew him to the sea. Already in his young life he was beginning to learn the skills of sailing and navigation that would later assist him in his final quest. The first of his experiences as a young apprentice was to the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea, in the area of Constantinople, the seat of the Christian religion that was conquered shortly thereafter by the Turks.

In later voyages, Columbus sailed to England and is believed to have traveled as far as Iceland. Some historians think that here he came in touch with the stories of the Vikings’ exploits into North America.

It was, however, well known that beyond Iceland lay the bleak shores of Greenland. And the existence of land even farther to the west was an accepted fact, though it was seldom visited. Nearly five centuries had passed since Norse adventurers had first touched on the coast of Labrador, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and possibly New England, settling briefly before being driven out by hostile natives. But in the intervening time Icelanders had continued to make occasional voyages there to collect timber. In the hunt for new fishing grounds, those faraway lands were now assuming new significance and Columbus undoubtedly heard much about them as he haunted the quays, taverns and counting houses in Bristol.

Just as historians have argued endlessly over the birth date and ancestry of Columbus and whether he was a merchant or a sailor, whole books have been devoted to the question of whether he sailed as far as Iceland. Later in life he sometimes said he had done so, though at least once he mentioned only England, not Iceland.4

At one point, Columbus joined a trading party that was going to England. Their vessels sailed from Genoa, around the Strait of Gibraltar, and then up the Atlantic Ocean. Off the coast of Portugal, they were attacked by pirates, and the ship upon which Columbus sailed was sunk. Although many drowned in the battle, Columbus fortunately made his way to shore and later on to Lisbon.

Columbus’s Marriage Is Beneficial to His Goal

Once in Lisbon, Columbus began to avail himself of the opportunity to learn greater details about navigation. He put together information and made a living, along with his brother Bartolome, as a mapmaker. In a local convent where Columbus had become accustomed to worshiping, he met Felipa Moniz Perestrello, who would become his wife.

Living with her mother, who was virtually penniless, Felipa had little to offer beyond her charm and high social rank. Her father was an Italian who had migrated to Portugal, married well and been awarded the hereditary governorship of the small island of Porto Santo, near Madeira. The island never flourished; he had died there some twenty years before, and the governorship had gone to the husband of Felipa’s sister.

Columbus, however, could not afford to be fussy. He was a humble, good-looking stranger whose main possession was his high ambition. But this apparently was enough to attract Dona Felipa, and their marriage took place in the convent chapel, probably in the autumn of 1479.

Columbus had moved a step up the ladder. His wife’s nobility gave him standing in the community, transforming the itinerant Genoese seafarer into a figure of social substance with an important brother-in-law.5

New Voyages and Knowledge

Portugal sought to push its knowledge of the new frontiers and sent its ships south to the coast of Africa. Columbus was able to join these expeditions that added additional knowledge and curiosity to his already-growing uneasiness. He probably became more interested in what lay to the west as he gained this new experience. He said, “In sailing frequently from Lisbon to Guinea southward, I noted with care the route followed, and afterwards I took the elevation of the sun many times with quadrant and other instruments.”

Perhaps the most important insight gained by Christopher Columbus was his discovery concerning the great oceanic wind system. Along the Portuguese coasts and in the Madeira Islands, he had experienced the strong west winds that brought flotsam ashore from the direction of the sunset. Then, on voyages to Africa and the Canary and Cape Verde Islands, he felt the steady northeast trades. In this, Columbus reasoned, lay the secret to an Atlantic round trip: Drop down south to go westward with the trade winds, and return at a higher latitude with the westerlies.6

More Evidence

New information began to flood Columbus’s mind when he was asked to go to the island of Madeira to handle the affairs of some important Portuguese families. Here he began to note the patterns of the ocean and the winds:

While he was married to Felipa the idea began to grow. In every port of call Columbus sifted more scraps of supporting information from the waterfront buzz that was the medieval equivalent of a daily newspaper. He heard of seamen finding lengths of a cane, unknown to Europeans, floating in the sea, and pieces of wood evidently carved by human hands. In the Irish port of Galway he heard a story of bodies with so-called Oriental features found in a drifting boat. In the Azores he heard a similar story and saw strange pinecones washed up on the beach. Sailors spoke of mysterious islands glimpsed on some far horizon but lost again. Such stories were widely believed because the Atlantic was then supposed to be dotted with islands.7

Charts and Documents Create Additional Information

Columbus later returned to Portugal with Felipa in 1480, and a son, “Diego,” joined their family. While Columbus was there, he reportedly obtained some important information that was later found in his personal papers:

Columbus acquired from his father-in-law’s widow the charts and document describing the Atlantic voyages. These excited him, stirring his developing interest in ocean exploration.

Perhaps among those papers he discovered a copy of a letter by Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, a respected Florentine geographer and mathematician, dated June 25, 1474, that was to be sent to Portugal’s king. Another copy was found in the 19th century, at the back of one of Columbus’s books and containing Latin errors typical of him.8

Some handwriting experts who have examined the documents believe that in addition to the Latin errors that were made—errors that were common to Columbus—the handwriting was his. Toscanelli's letters contained information about Marco Polo's travels to the Far East and suggest how a voyager might go to the East by traveling west. Historians surmise that Columbus had obtained a map in addition to the letter and that both were a part of his personal possessions: “With the letter was a map incorporating Toscanelli's theories. Columbus probably possessed a copy. The Toscanelli map and letter either began or confirmed Columbus's interest in the idea of sailing west across a relatively narrow Atlantic directly to Asia.”9

The Pieces of the Puzzle Start to Fit

The maps, coupled with the experience he had gained along the coasts of Africa and Madeira, must have helped Columbus put together information regarding what lay to the west.

Columbus now had formulated his plans, and he petitioned King John II of Portugal for ships and backing to make his expedition. The king secretly sent a ship to test Columbus’s theory, and the ship returned with no success. With his petition denied, Columbus’s life received another challenge when his wife Felipa died.

Columbus decided to go to Spain, where Felipa's sister lived, with the thinking that she might be able to care for his young son Diego while he pursued his quest with the court of Spain.

Spiritual Influences and Motives

After arriving at the port of Palos, Spain, Columbus heard about a local Franciscan monastery, Santa Maria de la Rabida, that housed travelers. Here he became friends with Antonio de Marchena, who was to become an important person in helping Columbus to achieve his goal.

Marchena belonged to the Observantines, a group with an apocalyptic agenda; looking to the end times, when all the world would be converted to Christ, they hoped to recover Jerusalem’s holy places from the Muslims. Significantly these tenets became ruling motives in the life and writings of Columbus.

The Genoese mariner and the friar became fast friends. Columbus received spiritual and intellectual counsel from Marchena, an educated man and dedicated cosmographer, and possibly accepted help in composing and reading Latin and Castilian. More important, the friar had access to the power structure at court.10

Some historians feel that Columbus's voyages were for selfish purposes so he could advance his personal ambitions. That could easily be theorized if we fail to understand that the reason he had that motivation resulted from his desire to use the proceeds to liberate Jerusalem from the Muslims.

Historical documents show that Columbus spent time in prayer and in attending mass. Apparently, the time he spent at La Rabida served to intensify his spiritual sensitivity and his faith. Some scholars may have questioned his sincerity, but those who knew him did not seem to question it.

Even beyond personal piety, Columbus began to believe that his plan for Atlantic navigation was divinely supported, that it was somehow connected with God’s purpose for the world.

Antonio de Marchena wrote a letter on his behalf to Hermando de Talavera, the queen’s confessor. The letter asked the right to petition the royal council, which made recommendations to the crown.11

The writings of Columbus clearly indicate that he felt and acknowledged the promptings of the Spirit. Although some scholars may doubt the source of his motivation, none deny that he was on a crusade to accomplish his goals.

“I plow ahead,” he said, “no matter how the winds might lash me.”12

The prompting of the Spirit was definitely a part of Columbus’s life. Although some scholars may doubt the source of his motivation, none of them deny that he was on a crusade to accomplish his goals.

The Vision of a Lifetime Is fulfilled

Thus began the start of a seven-year quest to seek approval for his voyage. Columbus spent time making presentations; and when he appeared to be rebuffed, he was told that his expedition could not be supported. In 1492, he made one more attempt to present his project to the monarchy. They turned it down—but then approved it. The vision of a lifetime was now going to be fulfilled:

Again his plan was rejected, then reconsidered, and finally approved. On April 17, 1492, he signed a contract with Castile that gave him the titles he had asked for and one-tenth of all revenues from his discoveries. But Columbus never lost sight of the crusading aspect of his journey; he intended that the forthcoming Indies revenues should primarily be dedicated to the recovery of Jerusalem from the Muslims.13

Recent discoveries of information that was contained in a book printed in 1477, which had belonged to Columbus’s personal library, give some very interesting insight into the vision he had of his voyage and his personal feelings about life and immortality. Personal notes in the margin and handwritten pages at the end are very informative: “Here, Columbus had placed his master plan on paper. His notation on the right side refers to the sinus sinarum, the sea of China. Combined with the note on the left, he indicates that the Far East is also the Far West. Never, could [anyone] come closer to the mind, and driving vision, of Christopher Columbus.”14

Religious Conviction and the Influence of the Scriptures

Those who have studied Columbus’s life have also concluded that some of Columbus’s original “papers” had been sewn into the end of one of his most-used books: “These pages evidently hold the earliest surviving writings of Columbus. On one he lists the Old Testament books and prophets on whom he relied. He tells of the Holy Spirit which with rays of marvelous brightness comforted me with His holy and sacred Scriptures, in a high, clear voice. The Scriptures spoke strongly to him; passages about the East, the conversion of heathens, the recovery of holy Jerusalem, and the approaching end times, when Christ would come again.”15

Columbus's writings and margin notes reflect a deep spiritual sensitivity to the scriptures and to their influence upon his life and goals: “One entry affirms his staunch Christian belief in life after death. Underlining Pliny's skeptical statement that mortals could not become immortal, he declares in the margin: ‘This is untrue.’”16

“Indians” and the Discovery of an Advanced Civilization

Not until his fourth voyage did Columbus discover the mainland of South America. His first landfall was in the Bahamas on the island that he named “San Salvador” (Holy Savior). The Indians whom he met were described by him as “‘naked as when born of their mothers, most handsome men and women.’ They were so white that if they protected themselves from the sun and air, ‘they would be as white as in Spain.’”17

These were Arawak Indians, and he later met the Taino tribe and the Caribes. The two former tribes were

gentle people who were easily enslaved, the Caribes were fierce and described as being “cannibalistic.”

Columbus later “enslaved” the Arawaks and Tainos by requiring them to produce a certain amount of gold. This event has been a subject of great criticism of Columbus; however, the outcome is easy to understand when we recall his religious zeal to free Jerusalem from the Muslims and his desire to make a good impression on the Spanish monarchs.

From the Bahamas, Columbus sailed south to the north coast of Hispaniola. On Christmas day, the Santa Maria ran aground off the coast of the island. This tragedy required a change in plans. The two ships could not carry the crew of the three ships, and thus they determined that they would build a fort and leave part of their crew until they returned on the next voyage.

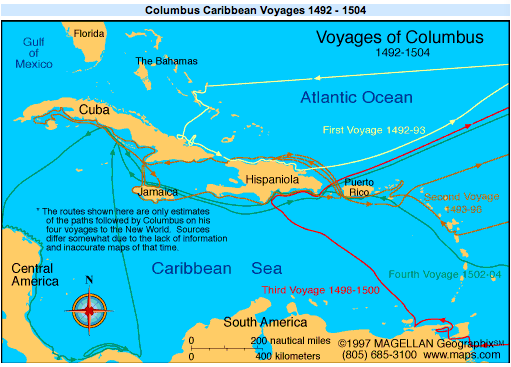

Columbus made a total of four voyages to the West Indies. On his second trip, he discovered the pattern of the westerly trade winds and was able to make the trip in just twenty-one days. But not until his fourth voyage in 1502 did he discover the mainland of South and Central America when he sailed along the coasts of Venezuela and Panama and as far north as Costa Rica.

During Columbus’s third voyage, the tide of Spanish opinion began to turn against him:

Columbus’s third voyage in 1498 did not end happily. With a few volunteers Columbus discovered Trinidad and made his first landfall on the continent of South America. But when he reached Santo Domingo, he found mutiny in progress. Two ships were sent back to Spain to report the rebellion. In the meanwhile malcontents had reported Columbus was a tyrant and Francisco de Bodadilla was sent from Spain to investigate. Although Columbus had succeeded in stopping the rebellion, in October, 1500, he was sent with his brother back to Spain under arrest.18

Columbus was eventually found to be innocent of the charges and was given permission to make his fourth voyage. The rigors of his life had taken their toll, and he died in 1506. His desire was to be buried in Hispaniola, and in 1536, his body was taken from Spain and buried in a cathedral in Santo Domingo where it lies today in the first cathedral that was constructed in the western hemisphere. However, some historians believe that Spain was his final burial location.

Columbus Fulfills Prophecy

Despite the criticism of many, Columbus remains the man who prepared the way for the colonization of America and also paved the way for the restoration of the gospel through the Prophet Joseph Smith. Though he had weaknesses, as do all mortals, Columbus clearly followed the promptings of the Spirit and fulfilled prophecy in the process.

Who then was Christopher Columbus? A man both of and beyond his time, he bestrode the boundary between ages, possessing a nature rich in contradictions. This most singular sailor was in fact an empirical mystic, within whom the temporal and the spiritual warred. A plebeian who rose to noble state, he inwardly disdained the citadels of power while ardently seeking their privileges. Not highly educated, he deeply admired learning. Believing his God would open for him the sea road to the earthly paradise, he felt empowered on his mission by the Holy Spirit.

At the end he had triumphed over his detractors to conquer the Sea of Darkness. While pursuing one vision, he inadvertently realized another: the outreach of Europe into a hitherto separate, but henceforth vastly wider world.

Truly this uncommon commoner Christopher Columbus began a process that, in words from a passage in one of the books of Esdras, “shook the earth, moved the round world, made the depths shudder, and turned creation upside down.”19

Columbus had a great effect upon preparing the world for the restoration of the gospel. He left his imprint especially upon the islands of the Caribbean and throughout the western hemisphere. Therefore, if we are to understand how the restored gospel began in the Caribbean, we must give honor and praise to that great navigator, Christopher Columbus.

In December of 1978, Elder M. Russell Ballard, as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, dedicated Jamaica and the Dominican Republic for the teaching of the gospel. Those events prompted personnel of the Church to determine whether Puerto Rico had been dedicated for the same purpose. Puerto Rican Church leaders and members had no memory or record of any dedication. Elder Joseph B. Wirthlin of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles had replaced Elder Ballard as executive administrator, and when Elder Wirthlin researched the matter at Church headquarters, he determined that Puerto Rico had never been dedicated for the teaching of the gospel.

Therefore, on July 29, 1979, at a beautiful site near the city of Caguas where the Church had property for a future chapel, Elder Wirthlin dedicated Puerto Rico for the teaching of the gospel. Prior to the dedication, he made the following comments: “I have been thinking today—I suppose the spirit of Christopher Columbus has been on my mind. I would think that the Lord would permit him to be present today, for he loved the Caribbean Islands and was here in Puerto Rico on many occasions. He was a great and noble man, inspired by the Lord to navigate the dangerous Atlantic and to make possible the restoration of the gospel.”

In the dedicatory prayer, Elder Wirthlin said: “We are grateful for Christopher Columbus, who was an inspired servant of destiny. Nephi, who received a revelation concerning him states: ‘And I looked and beheld a man among the Gentiles, who was separated from the seed of my brethren by the many waters; and I beheld the Spirit of God, that it came down and wrought upon the man; and he went forth upon the many waters, even unto the seed of my brethren, who were in the promised land.’ Columbus fulfilled this prophecy and set forth on these shores.”

Later in the dedicatory prayer, Elder Wirthlin asked the Lord to bless Puerto Rico—as a land of promise: “Bless this island as a land of promise. May freedom always prevail. May no evil influence take away this priceless freedom that gives liberty to all those who worship thee and thy beloved Son. We pray that this land may remain under the protecting umbrella of the Constitution of the United States, so that this people will remain free.”

With the blessings of the Lord having been pronounced upon Puerto Rico by a servant of the Lord, the work began in the new Puerto Rico-San Juan Mission. The promised blessings by Elder Wirthlin have been fulfilled, and the mission has become a very fruitful area of the kingdom.

The Discovery of “America” by Columbus

Those of us who live in the United States of America are routinely taught during our public-school education that “Columbus discovered America,” and we are proud to be associated with Columbus in that respect. However, we fail to realize that Columbus technically did not “discover” the continental United States as we know it today. That is, he never cast his eyes on the eastern seashore of the United States, and he never set foot on the soil of the continental United States.

But he did discover “America” as it was defined initially. Prior to the twentieth century, “America” was defined as shown in Noah Webster’s 1828 dictionary, American Dictionary of the English Language:

One of the great continents, first discovered by Sebastian Cabot, June 11, O.S. 1498, and by Columbus, or Christoval Colon, Aug. 1, the same year. It extends from the eightieth degree of North, to the fifty-fourth degree of South Latitude; and from the thirty-fifty to the one hundred and fifty-sixth degree of Longitude West from Greenwich, being about nine thousand miles in length. Its breadth at Darien is narrowed to about forty-five miles, but at the northern extremity is nearly four thousand miles. From Darien to the North, the continent is called North America, and to the South, it is called South America.20

Thus, early in the history of the United States, “America” encompassed all of what we refer to today as North America, Central America, and South America. In that respect, then, Columbus did, indeed, discover “America,” even though he never set foot on territory of the continental United States of America.

Those facts about Columbus are important because some Book of Mormon readers maintain that all New World lands of the Book of Mormon are located in the United States. Further, such readers often also maintain that all Book of Mormon references to “promised land” and “land of promise” point exclusively to territory within the continental United States.

However, as noted previously, “The Spirit of God . . . came down and wrought upon [Columbus]; and he went forth upon the many waters, even unto the seed of my brethren, who were in the promised land” (1 Nephi 13:12; emphasis added).

Obviously, Book of Mormon readers who advocate that all the New World lands of the Book of Mormon are located in the “promised land” of the United States of America do so erroneously. That is, the “promised land” of the Book of Mormon cannot be territory located exclusively in the United States of America because Columbus never, ever “went forth” to any of the “Remnant Seed” who were residing in the continental United States. The “promised land” of the Book of Mormon, therefore, is, indeed, “America” as defined at the time Joseph Smith translated the Book of Mormon—all the territory of North America, Central America, and South America as we know them today. Further, we must look beyond the territory of the continental United States in any search for the New World location of the lands and events of the Book of Mormon.

Those who have lived in the Caribbean have learned to appreciate Columbus’s part in discovering America. We cannot read about the man and his determined motivation without developing a feeling and a kinship for him. I feel that one day when we meet, I will know him; and I look forward to visiting with him about his part in the restoration of the gospel.

Notes

1. Eugene Lyon, “Search for Columbus,” National Geographic Magazine 181, no. 1, January 1992, 30.

2. John Dyson, Columbus: For Gold, God, and Glory (Toronto: Madison Press Books, 1991), 14.

3. “Columbus,” BYU Quincentennial Newsletter, “Europe Encounters America,” Quincentennial Exhibition, April 1992.

4. Dyson, Columbus, 50.

5. Ibid., 55.

6. “Search for Columbus,” 26–27.

7. Dyson, Columbus, 64.

8. Lyon, “Search for Columbus,” 25.

9. Ibid., 26.

10. Ibid., 30

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid., 32.

13. Ibid., 36–37.

14. Ibid., 33.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid., 34.

17. Hans W. Hannau, The Caribbean Islands (Miami: Argos, 1972), 39.

18. Ibid., 8.

19. Lyon, “Search for Columbus.”

20. Noah Webster, American Dictionary of the English Language (New York: S. Converse, 1828), s.v. “America”; emphasis added.